Treasure near Jesus-era Galilee site linked to forgotten Jewish uprising, archaeologists say

A hoard of 22 bronze coins from the 4th century A.D. was found at Hukok, near Capernaum, offering rare evidence tied to the Gallus Revolt.

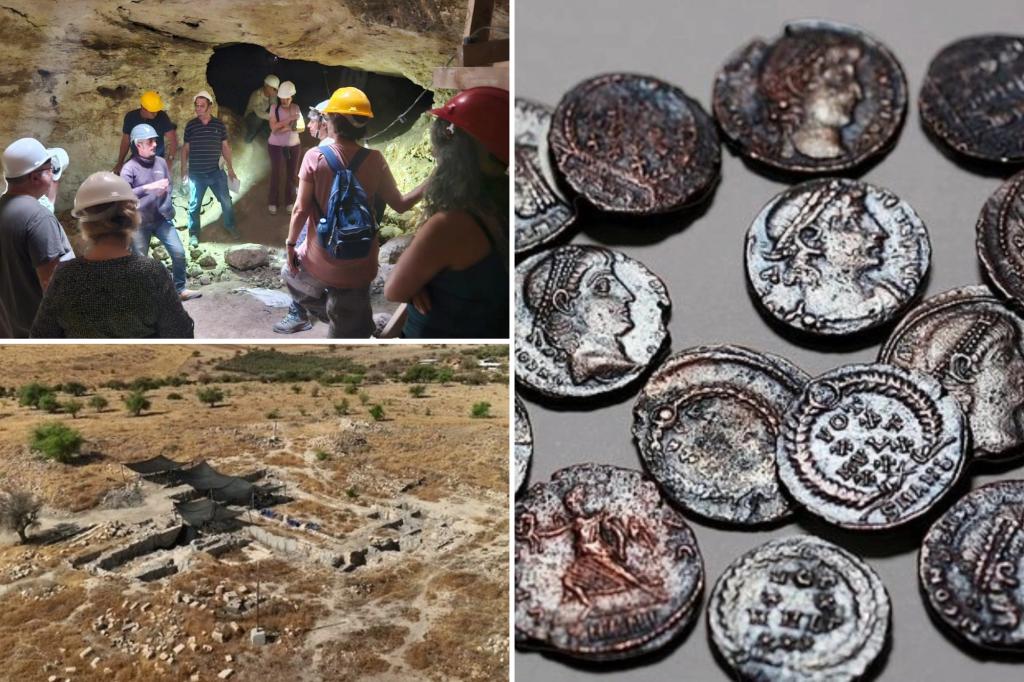

A trove of 22 bronze coins dating to the 4th century A.D. has been found in a small crevice inside an underground hiding complex at Hukok, a kibbutz in northern Israel near Capernaum, archaeologists said. The coins were uncovered by volunteers during a tourism-development project, and researchers date the hoard to more than 1,600 years ago, linking the discovery to the Gallus Revolt, a Jewish uprising against Roman rule in 351-352 A.D.

IAA researchers said the coins were located in a deep crevice at the end of a narrow tunnel leading to an underground hiding complex. Hukok sits roughly three miles west of the ancient fishing town of Capernaum in the Galilee region. The hoard’s placement and the complex’s construction suggest the owners hid the coins with the expectation that they would return after the danger had passed.

The IAA notes that the hiding complex appears to predate the Gallus Revolt in the 4th century and that the tunnels may have been dug earlier, during the Great Revolt in the first century A.D. or the Bar-Kochba Revolt (132-136 A.D.), with later generations reusing the same tunnel system. The discovery underscores how hideouts carved into the landscape were repurposed over centuries as new crises arose in the region.

This find provides, in all probability, unique evidence that this hiding complex was used during another crisis—during the Gallus Revolt—a rebellion for which historians have only scant documentary evidence. Researchers said the coins’ context helps illuminate how communities coped with upheaval in the Galilee during late antiquity.

We are speaking about a moment that blends archaeology, history and public engagement,” said Uri Berger, an IAA researcher involved in the excavation. “The hoard offers a snapshot of how people prepared for danger and hoped to recover their assets later.”

The discovery was made by volunteers who were helping to advance tourism development at Hukok, turning what began as a dig into a broader educational experience. Einat Ambar-Armon of the Israel Antiquities Authority said the project highlighted the public’s connection to its heritage and reinforced a sense of belonging to the past. “Fortunately, it was the many volunteers excavating the hiding complex who actually uncovered this important treasure, and they enjoyed this great moment of discovery,” she said. “The excavation thus became not only an important scientific event, but also a significant communal educational experience.”

Eli Esco-—note: director’s quote included in source material—the IAA director, said the agency hopes Hukok will become a magnet for visitors from Israel and abroad. He added that the public should be able to enjoy the hidden treasures of the site, as researchers continue to study the layers of history embedded in the underground network. “We are working together so that the entire public can enjoy the hidden treasures of this site.”

The IAA emphasized that the site’s layered history—its long use as a hiding place across multiple revolts—adds depth to the region’s narrative of resistance and resilience. As archaeologists continue to document and interpret the Hukok complex, scholars aim to place the coins within a broader map of fourth-century Mediterranean upheaval and Jewish-Roman-era life in Galilee. The find, while modest in size, offers a tangible link between a landmark in the Galilee landscape and the turbulent centuries that shaped the region’s communities.

For readers and researchers, the Hukok discovery adds a fresh, material thread to the story of Galilee during late antiquity, illustrating how a landscape can hold long-hidden stories and how modern volunteers and professional archaeologists together reconstruct them for future generations.