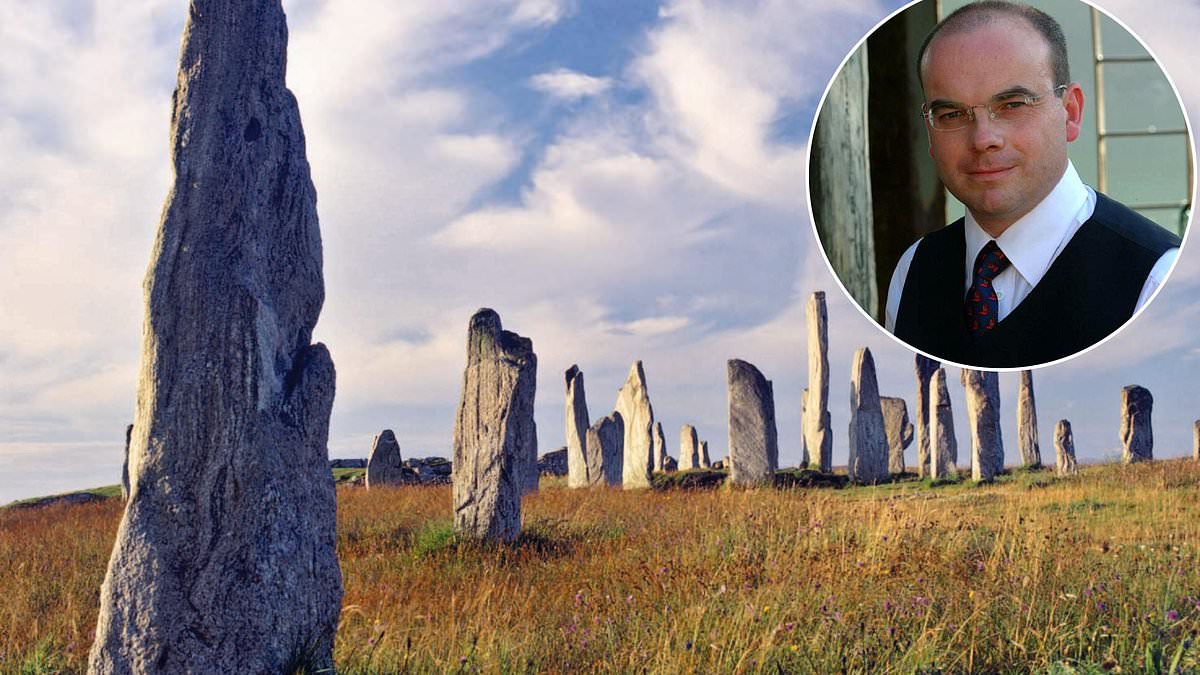

Turning Peat into Light: The Pontings and the Callanish Stones

In the Outer Hebrides, a couple’s 1970s fieldwork reshaped knowledge of the Callanish Stones and the region’s prehistoric trade and ritual.

In December 1974, a young English couple settled in Lewis with the intention of building a family life and perhaps a degree of self-sufficiency. Gerald Ponting, a biology teacher, and his wife Margaret moved to Callanish with two small children, drawn by a sense that the island’s famed Standing Stones held answers not yet written about them. What began as a hobby—ambling among the circle, cairns, and peat beds—soon grew into a scholarly pursuit. By the late 1970s, the Pontings had established themselves as the leading outsiders who could hold a conversation with local memory and the material record about Callanish. By the early 1980s, their fieldwork yielded a string of notable discoveries that reshaped how researchers understood the site and its wider landscape.

The Pontings operated in a time before personal computers and easy access to archives. They described, with a mix of practicality and wonder, the challenges of researching from a remote parish where roads were single-track, supermarkets scarce, and even television slow to arrive. They traveled to London to consult archives at the Public Records Office, and at times they had to wait weeks for a response when seeking notebooks and minutes recorded in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The process could feel like a test of patience: the right file might not be in the first box requested, and the pace of discovery in Kew could feel like treacle. On Lewis itself, artifacts frequently moved to metropolitan museums, complicating locally anchored scholarship. Yet the Pontings pressed on, turning their curiosity into a body of work that would outlive them.

Their most enduring contribution, New Light on the Standing Stones of Callanish (1977), helped establish a framework for interpreting the monuments not as isolated curiosities but as part of a broader Neolithic and Bronze Age landscape across Lewis. In the years that followed, they documented additional sites in the Callanish complex and beyond, including eleven other stone circles in the region and related megalithic remains near Achmore, Garynahine, Shawbost, and beyond. Through field notes, careful measuring, and a willingness to revisit and revise earlier interpretations, the Pontings showed that the Callanish stones were embedded in a dynamic, living landscape of peat bogs, coastlines, and changing communities.

The Pontings’ work extended beyond the stones themselves to the peat that burys history beneath the island. Peat, which blankets Lewis to depths of ten feet or more in some places, preserved both organic and wooden remnants that might otherwise have vanished in the damp air. The couple’s observations and field reports helped illuminate how peat cutting could reveal, preserve, and sometimes threaten buried evidence. They emphasized that wood uncovered in water—where it could survive longer than in air—deserved special care, a practical insight that guided later recovery efforts.

Among their most striking finds was evidence that a Stone in the Callanish complex had not always stood in its present position, a clue pointing to Victorian-era alterations at the site. They identified Stone 33A, long recumbent in the bog, and were instrumental in re-erecting it in its original socket. Their careful probing of drystone dyking around the stones recovered the missing tip of Stone 19, a discovery that helped correct the sequence of repairs and placements across the ensemble. These adjustments were not mere curiosities; they altered researchers’ understanding of how the Callanish site had evolved over time and what those changes said about past construction and landscape management.

Their findings helped shift the narrative around Lewis from a collection of isolated monuments to a connected tapestry of places with long-distance connections. The discovery that some stones had been moved or re-set in later periods underscored a continuity of engagement with these sites across generations. A practical conclusion of their work was a reminder that field archaeology in a fragile peat environment requires careful attention to the landscape, weather, and local practices to avoid disturbing fragile contexts.

The Pontings were not only fieldworkers; they were communicators who brought complex discoveries into accessible terms for local readers and visiting researchers alike. Gerald Ponting’s written reflections—recounted in his memoirs and in the Islands Book Trust edition Archaeological Adventures in the Outer Hebrides—document the rigors of late-20th-century fieldwork and the improvisational spirit that marked much of Scotland’s regional archaeology during that era. The Pontings’ published notes and Patience with archival requests helped cement their status as respected, if sometimes controversial, contributors whose work encouraged others to revisit the standing stones with fresh questions.

The late 20th century also recorded a physical reminder of the broader trade networks that spanned the Atlantic fringe. In April 1982, the MacMillan family of Shulishader unearthed a remarkable stone axe head from peat with its wooden haft surprisingly preserved. The axe head dated to roughly 2910–3490 BC, and its haft’s preservation was unusual in that it survived in a peat-logged context. The axe head, made of porcellanite from a known factory in County Antrim, suggested a surprising reach of trade networks or exchange routes that connected Lewis to continental sources far to the south and east. The artifact was later entered into national memory as part of Scotland’s broader Neolithic material culture collection, with the National Museum of Scotland serving as a repository for the find. The paper trail around the axe—its preservation, its dating, and its origins—helped anchor the Lewis landscape within wider prehistoric exchange networks that researchers continue to examine today.

The Pontings’ personal arc mirrored the arc of their scholarship. In 1983, Gerald and Margaret separated; they moved on to different lives, and Gerald left Lewis for the mainland in 1984, rarely returning. Yet they both continued to contribute to scholarship in their own ways, and Margaret’s passing in 2022 prompted obituaries in London papers that reflected on her long, quiet dedication to archaeological work. Gerald has spoken later of testing his own beliefs against Lewis’s landscape and culture, suggesting that the island’s history often proved more compelling than the alternatives.

Beyond the Pontings, the Callanish region remains a focal point for archaeologists and historians seeking to understand prehistoric life in the Western Isles. The main Callanish stone setting comprises a central main stone circle with ringed avenues, but the broader landscape features other circles and cairns, which collectively offer a portrait of a society that engaged with its environment over centuries. The peat bogs themselves preserve wooden and organics that would not survive in drier contexts, providing a rare window into the materials and technologies of the island’s earlier inhabitants. In the decades since the Pontings’ work, researchers have continued to study the wider field of stone circles, chambered cairns, and associated features around Callanish, Achmore, Garynahine, Shawbost, and other locales on Lewis, enriching the story of one of Scotland’s most storied archaeological landscapes.

The Pontings’ legacy lies not only in the findings themselves but in the method and perseverance they demonstrated. They showed that a local, patient approach—coupled with careful collaboration with local communities—can produce insights that challenge assumptions about how monuments were built, used, and maintained. The Callanish stones, once treated as a static, isolated monument, are now understood as part of a living, evolving landscape shaped by peat, sea, and people across millennia. Their work helped lay the groundwork for a more nuanced view of the island’s past—one that recognizes both the remarkable endurance of stone and the subtle ways in which peat and weather shape the stories those stones tell.