As AI Spreads Through Classrooms, Schools Rethink Homework, Tests and Definitions of Cheating

Teachers and universities are shifting assessments, drafting new policies and teaching AI literacy as student use of chatbots and translation tools blurs lines of academic honesty.

Artificial intelligence is transforming classroom practice across the United States, forcing educators to redraw the boundaries of academic integrity as students increasingly rely on chatbots and AI-powered tools to complete assignments.

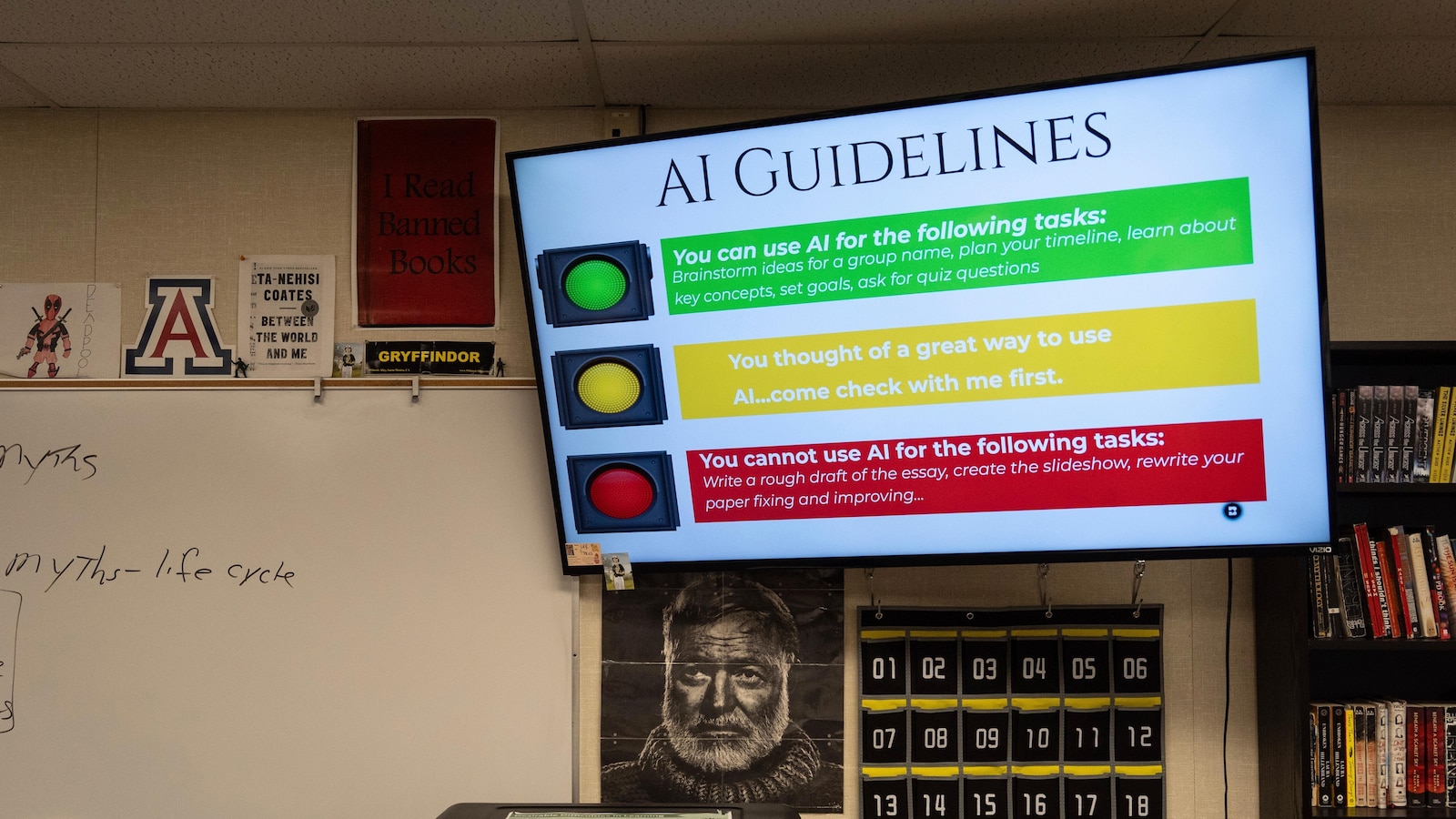

High school and college teachers say student use of AI has become so widespread that take-home essays and tests are often treated as invitations to outsource work, prompting a move to in-class writing, oral assessments and new syllabus language that clarifies acceptable AI use.

"The cheating is off the charts. It’s the worst I’ve seen in my entire career," said Casey Cuny, a 23-year English teacher and 2024 California Teacher of the Year, describing a wave of students who rely on AI for brainstorming, drafting and editing. Cuny said he now assumes that any assignment given outside of class may be submitted with AI assistance and has shifted most writing to classroom time, using monitoring software that can lock down student screens.

Teachers across different regions report similar changes. In rural Oregon, teacher Kelly Gibson said she no longer assigns multiweek take-home essays because, she said, that would be "almost begging teenagers to cheat." Gibson has increased in-class writing and incorporated more verbal assessments so students must explain their understanding of texts in person.

Students describe a gray area between legitimate study help and cheating. Some use chatbots such as ChatGPT for brainstorming, outlining or summarizing dense reading. Lily Brown, a college sophomore, said she relies on AI to outline essays and to translate difficult philosophical texts into simpler language. "Sometimes I feel bad using ChatGPT to summarize reading, because I wonder, is this cheating?" she said.

Schools and professors have responded in varied ways. Many institutions that initially imposed blanket bans on AI after the public debut of ChatGPT in late 2022 are now revisiting those rules. The term "AI literacy" has emerged as a common objective for the back-to-school season, with administrators urging faculty to provide clearer expectations on syllabi.

The University of California, Berkeley, for example, sent faculty new guidance that advises including explicit statements on course expectations for AI use and offered sample syllabus language for courses that require AI, ban it, or allow some uses. "In the absence of such a statement, students may be more likely to use these technologies inappropriately," the guidance said.

At Carnegie Mellon University, officials reported a sharp rise in academic responsibility cases linked to AI and have warned that many students do not realize they have crossed a line. Rebekah Fitzsimmons, chair of the AI faculty advising committee at CMU’s Heinz College, cited an instance in which an English-language learner used a translation tool to translate an assignment into English and was flagged by an AI detector after the tool altered phrasing.

Detecting AI assistance poses technical and procedural challenges. AI-generated text can be difficult to distinguish from student work, and available "AI detectors" have limitations and false positives. Faculty are increasingly cautious about accusing students of misconduct because of the risk of unfairly penalizing those who used tools unintentionally or in ways that their instructors did not prohibit.

Rather than pursuing strict prohibitions, some educators are altering pedagogy and assessment. Instructors are returning to in-person exams, requiring handwritten responses, or using lockdown browsers that restrict student actions during online quizzes. Others have embraced "flipped classroom" models in which traditionally assigned homework is completed under teacher supervision during class time.

Emily DeJeu, who teaches communication at Carnegie Mellon’s business school, said she eliminated writing assignments as homework and replaced them with in-class quizzes on laptops that use a lockdown browser. "To expect an 18-year-old to exercise great discipline is unreasonable," she said. "That’s why it’s up to instructors to put up guardrails."

Some teachers are also working to integrate AI into instruction. Cuny reported teaching students how to use AI as a study aid — uploading study guides to a chatbot to generate practice quizzes and explanations — with the goal of "getting kids learning with AI instead of cheating with AI." Students who learn those skills said they find the tools helpful but want clear rules so they do not risk violating course policies.

The variability of classroom policies creates confusion. Individual teachers often determine whether tools such as Grammarly are permitted; some permit grammar checks while prohibiting rewriting features. Students said they sometimes avoid asking instructors for clarification for fear that admitting to any AI use will flag them as cheaters.

Several colleges convened AI task forces over the summer to draft more detailed guidance for faculty and students. The resulting guidelines often stress that a blanket ban on AI is not sustainable unless instructors also change how they teach and assess work. Institutions are emphasizing clear syllabus statements, examples of permissible uses, and steps for faculty to detect and address suspected misuse while protecting students’ rights.

The rapid improvement and ubiquity of AI tools has prompted a debate about what constitutes learning and what constitutes cheating. Educators and academic leaders are grappling with how to preserve core learning outcomes while recognizing that AI will be a persistent part of students’ lives. Some view AI literacy as essential to preparing students for workplaces where such tools are commonplace; others worry that easy access to powerful writing and translation systems undermines the development of independent critical thinking and composition skills.

As the school year progresses, more classrooms are likely to test new combinations of policy, pedagogy and technology. For now, educators say the pressing task is to define acceptable uses, build reliable detection and adjudication processes, and design assessments that measure students’ understanding rather than their ability to command a chatbot. The outcome will shape not only how academic dishonesty is enforced but also how schools teach writing, research and critical reasoning in an era of pervasive AI.