How hard is it to become an influencer? Three people with zero followers find out

A BBC Radio 4 experiment follows three novices over three months, revealing the emotional cost and real-world outcomes of chasing online fame in the creator economy

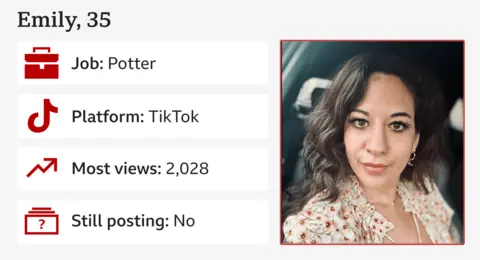

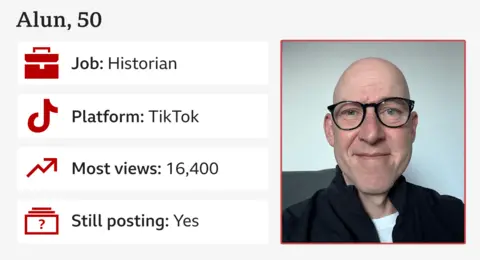

Social media has turned into a high-stakes arena where likes and views can define opportunities, yet the pathway to an audience remains elusive for most. In a BBC Radio 4 experiment, three people with zero followers—Emily, a potter and stroke survivor; Alun, a senior history lecturer; and Danyah, a theatre performer—set out to see if they could build a sustained audience on social platforms in just three months. The project underscores a broader trend in the creator economy, which is projected to be worth close to $500 billion worldwide by the end of the decade, while also illustrating the emotional and ethical costs of courting visibility in an algorithm-driven landscape.

Emily, who found pottery to be therapeutic after a stroke at 26, joined TikTok with the intention of reaching others who have faced similar challenges. Her early content, which focused on pottery and her cat, drew only a couple of views. Weeks of silence on the feed gave way to doubt about authenticity and purpose. Then a turning point arrived: a video about how pottery helped her recover that connected with thousands of viewers and drew messages of support from fellow stroke survivors. For Emily, the impact of those comments proved more meaningful than a surge of likes, signaling that her work resonated on a human level. Yet the moment also brought new pressures. She found engaging with a flood of comments overwhelming, and she wrestled with the feeling that she was performing rather than speaking from her true self. Discussing sensitive topics such as recovery from a stroke raised the stakes for her, with no margin for error in what she shared. As personal life challenges mounted toward the end of the experiment, she decided to pause posting for a while, leaving open the possibility of returning in the future.

Alun, a senior lecturer who specializes in early modern medicine and the cultural history of beards, joined the project out of a sense of duty to educate the public. His first video explaining why he loves history drew a modest crowd, but he pressed on, posting every few days. View counts rose gradually, with several videos reaching more than a thousand views, though none eclipsed that threshold. The numbers began to take an emotional toll: when views were low, he questioned his own value and wondered if his scholarly work was being supplanted by online metrics. A breakthrough video fetched more than 10,000 views, but the elation was tempered by a moment of self-scrutiny: he admitted that in the chase for views he had risked oversimplifying complex topics and felt uneasy about that simplification. The online backlash also appeared in the form of cruel comments about his appearance due to alopecia, prompting him to respond with a candid video about his condition. He found that his university could help expand his reach by sharing his content with prospective students, a move he described as a boost that complemented his academic work rather than replacing it. By the two-month mark, his total view count had climbed to hundreds of thousands, a level far beyond the readership of his academic articles, yet he remained resolute about continuing to post because of the broader visibility it provides for his scholarship and teaching.

Danyah, a theatre performer and producer, approached the experiment from the opposite end of the spectrum: she was comfortable on stage but unfamiliar with online formats. Her YouTube work emphasized longer, slower content, including meditation guides and poetic pieces scattered across London. Her first video ran eight minutes, and while early views were modest, she kept posting with enthusiasm. In a single month she produced about 50 videos, a pace that proved mentally draining and emotionally exhausting. She describes the experience as being consumed by the grind, likening it to an addiction that affected her everyday life. Yet the effort paid off gradually. By the third month, while the numerical rewards remained variable, the influx of kind comments and the occasional uptick in views helped her to keep going. The broader outcome remained mixed: the greater online presence supported increased ticket sales for shows and workshops, but the personal cost of maintaining a constant online rhythm weighed on her. She remains hopeful that she can balance the drive for visibility with the work she loves on stage, continuing to post beyond the experiment in the belief that a sustained online presence can amplify her live work without erasing the joy of performance.

Across the three stories, the experiment offers a grounded look at the realities behind influencer culture. The participants faced similar challenges: initial invisibility, the emotional labor of audience engagement, and ethical considerations around how much to simplify complex topics for a wider audience. It also highlighted the practical upsides of online reach, including opportunities to promote one’s work, build professional networks, and, in some cases, monetize a passion. The university’s rediscovery of Alun’s content and the visible boost for Emily’s and Danyah’s work illustrate how institutional and community support can intersect with individual creativity to broaden impact.

The BBC notes that the creator economy remains a high-stakes gamble for many would-be influencers, where a lucky break can translate into recognition and gigs, while the majority face a long, uncertain climb. The program also points to the emotional toll of online scrutiny, which can magnify insecurities, alter self-worth, and demand relentless time and attention. For Emily, the path meant confronting the tension between authenticity and performance, as well as the personal costs of maintaining an online presence while navigating recovery and daily life. For Alun, the thrill of viral moments coexisted with concerns about scholarly accuracy and the persistent pressure to measure success through views rather than scholarly impact. For Danyah, the grind of content creation threatened to overwhelm the love of performance, even as the numbers began to tilt in her favor and ticket sales rose.

The three-month journey does not offer a definitive blueprint for success in social media, but it does provide a snapshot of what it takes to attract an audience in a space governed by algorithms, feedback loops, and rapid public commentary. It also raises questions about how institutions, peers and audiences can support creators who aim to use social platforms to educate, entertain or connect people in meaningful ways. As the creator economy grows, the experiences of Emily, Alun and Danyah remind viewers that online visibility is not just about reach—it is also about responsibility, resilience, and the balancing act between personal well-being and public success.