Prison drone smuggling surge tests detection technology as authorities confront limits on countermeasures

Federal incidents reach 479 in 2024; states rely on detection and confiscation as FAA rules limit responses. South Carolina leads in detection systems amid evolving drone-smuggling tactics.

Drone incursions at U.S. prisons are rising, with federal facilities reporting 479 drone-related incidents in 2024, up dramatically from 23 in 2018, according to the Federal Bureau of Prisons. The scale of the problem is compounded by rules that constrain how authorities can respond. The Federal Aviation Administration treats drones as registered aircraft, which makes it illegal for states to shoot them down or jam their signals. Instead, states rely on detection and confiscation of drones and any contraband they carry, while investigators trace the operators through flight data and other records.

South Carolina has become a focal point in this evolving landscape. The state’s Department of Corrections has developed one of the nation’s most comprehensive drone-detection programs for its medium- and maximum-security prisons. In 2022, the state logged 262 drone incursions, up from 69 in 2019. Joel Anderson, the department’s director, said the agency is leading the nation in developing detection systems. When a drone flies over a facility, select prison staff receive a cellphone alert, and a dedicated drone-response team quickly converges on the drop location. Within minutes, the drone is out of sight unless it crashes or the team traces it back to the operator. The department reports drones have been caught in nets, snagged on fences, or crashed on the yard, and the confiscated drones yield in-flight data that helps investigators reconstruct paths, previous missions, and the images created during those flights.

Smuggling capabilities have grown more sophisticated in recent years. Drones that once carried about four pounds at top speeds near 45 mph now include heavy-lift machines capable of hauling 25-pound payloads at more than 75 mph, delivering contraband over prison fences. Anderson noted that at times there can be nights with back-to-back drops as operators shuttle drones between the controller and the facility. He also stressed that many pilots are former inmates who retain inside knowledge of the facilities and often rely on illegal cellphones smuggled inside to coordinate with outside handlers.

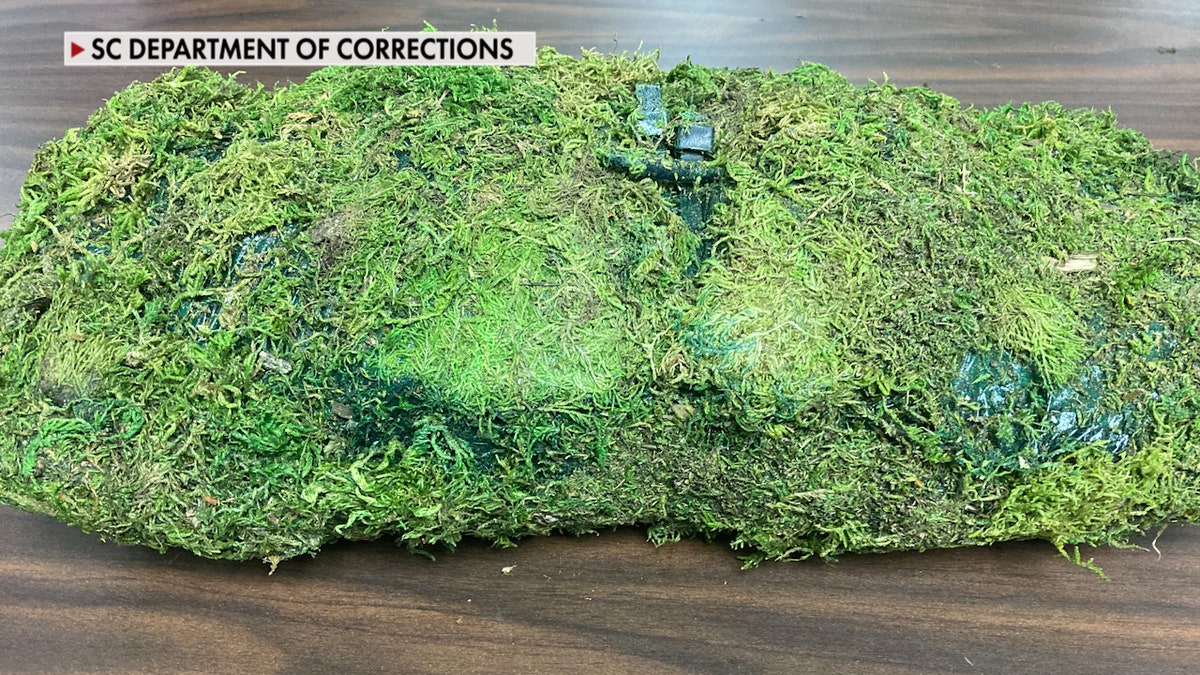

Authorities say criminals frequently camouflage their payloads to evade distant detection. Drones may be tucked with grass-like materials or other disguises to blend into outdoor yards. In one notable instance described by officials, a drone captured a photograph of a resident’s mailbox, a finding that helped investigators connect the drone to a specific operator. The common thread across cases is the reliance on illegal cellphones inside prisons, which drives much of the smuggling network and has prompted discussions about radio-jamming as a potential countermeasure.

States, for their part, cannot bring down a drone in flight. The FAA’s prohibition reflects safety concerns for people inside and outside prisons, including the risk that a disabled drone could drift into nearby neighborhoods. Instead, authorities emphasize detection at the perimeter, confiscation of the device and its payload, and forensic analysis of flight data to trace the operator’s location and connections. The threat is underscored by estimates that a single fentanyl-laden drone payload could be enough to incapacitate an entire facility or cause mass harm if released in a yard.

In parallel, U.S. regulators are weighing broader countermeasures. The Federal Communications Commission is examining the possibility of allowing states to deploy radio-jamming technology to block inmate communications with outside contacts. If approved, the move could target the illegal cellphones that fuel many smuggling operations, though it would raise regulatory and civil-liberties questions. Anderson praised corrections staff for their steadiness, noting that their work inside facilities is essential and that drones are often the symptom of a larger problem: the presence of unauthorized devices that enable illicit networks.

South Carolina’s approach has yielded tangible results. The state has integrated drone-detection capabilities with a rapid-response protocol that alerts a targeted group of staff when a drone is overhead and dispatches a drone-team to the drop location. Forensic analysis of recovered drones and their flight histories helps investigators connect devices to operators and plans. The program illustrates how technology, governance, and enforcement are converging in correctional settings as drone capabilities continue to evolve.

Even as drones grow more capable, the underlying challenge remains: countermeasures are constrained by federal rules, and illicit networks persist outside the walls of facilities. The evolving dynamic has spurred officials to emphasize detection, data analytics, and targeted enforcement, while regulators and lawmakers consider additional tools that could reduce the incentive to smuggle via air. In South Carolina and elsewhere, the integration of technology with disciplined operational procedures offers a path to reducing incidents and holding pilots accountable, even as new drone designs and tactics emerge.

Ultimately, the drone-smuggling challenge in American prisons highlights a broader trend in Technology & AI: how advanced sensing, data analysis, and automated response systems are reshaping public-safety operations, even as policymakers weigh the risks and benefits of the tools that enable them. As drone technology and communications networks continue to evolve, prisons and regulators will need to stay ahead with robust, legally sound, and technically effective countermeasures.