Schools Seek to Reverse Pandemic Setback as Girls Fall Behind Boys in Math

Dallas-area STEM school recruits balanced sixth-grade class as educators nationwide work to rebuild girls’ interest and performance in math and science after COVID disruptions.

Girls’ math performance and interest in STEM fields slipped during the COVID-19 pandemic, and schools are now mounting efforts to recover lost ground by creating hands-on learning opportunities and recruiting more female students into science, technology, engineering and math programs.

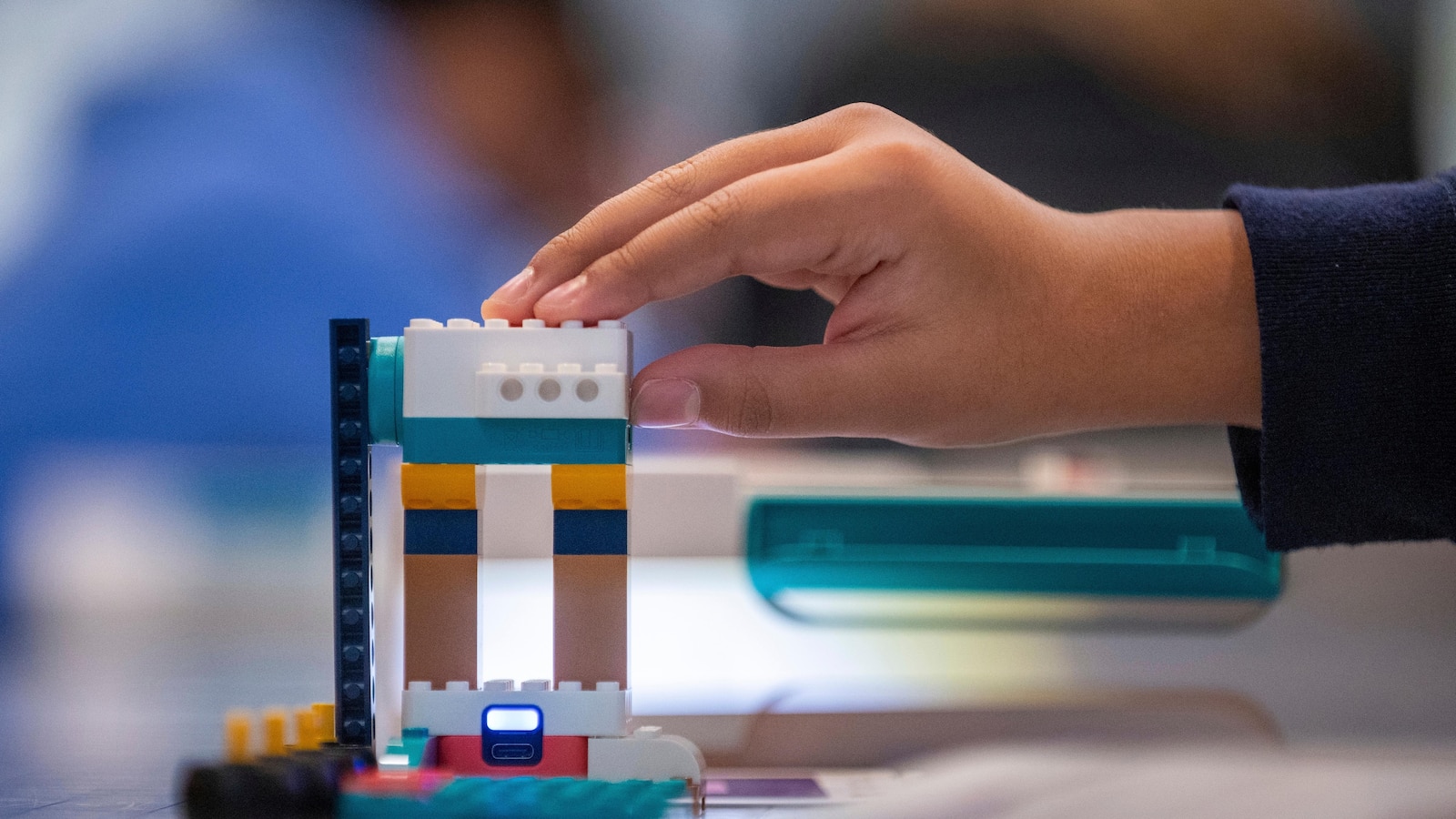

At de Zavala Middle School in Irving, Texas, four sixth-grade girls crouched around a workshop table puzzling over a Lego machine they had built. The students had been instructed that in the building process “there is no such thing as mistakes. Only iterations,” and they methodically adjusted components when a purple card failed to trigger a light sensor. When a student held an orange card over the sensor, the machine activated and another student, Sofia Cruz, exclaimed, “Oh! Oh, it reacts differently to different colors.”

De Zavala opened this school year as a choice school with an explicit STEM focus and recruited a sixth-grade class that is half girls. School leaders said they hope early exposure to engineering and technology will encourage girls to continue with STEM subjects as they progress through middle and high school. In contrast, some of the school’s higher grades — whose students enrolled before the STEM emphasis — have elective STEM classes with just one girl enrolled.

The experience at de Zavala reflects a broader pattern educators and school administrators have observed nationwide: the pandemic disrupted classroom instruction and extracurricular opportunities that often sustain and build student interest in math and science, and girls’ gains in these areas have lagged. Schools and districts have begun retooling curriculum, launching targeted recruitment for girls in STEM tracks, and emphasizing hands-on, collaborative projects intended to make math and engineering more engaging.

Educators at de Zavala emphasized iterative, project-based learning as a strategy to build confidence and problem-solving skills. By framing setbacks as part of the design process, teachers aim to reduce the stigma of failure and increase persistence among students who might otherwise opt out of advanced math and science courses.

District officials and school leaders say there is extensive work ahead to rebuild both performance and interest. The pandemic-era shift to remote learning, interruptions to in-person tutoring and extracurricular STEM clubs, and reduced access to lab equipment and mentorship opportunities are among the challenges schools cite when explaining the setbacks. Recovery efforts include expanded after-school programs, partnerships with community organizations and industry, and proactive outreach to families to promote female participation in STEM offerings.

Parents and educators at de Zavala described the school’s first STEM year as an early test of strategies intended to reverse the trend. Recruiting a cohort with gender balance at the entry level is intended to normalize female participation in higher-level STEM electives later on. School officials said they will monitor course enrollment and performance data as students move into upper grades to assess whether the approach increases retention and achievement among girls.

The rebuilding process is unfolding as districts across the country evaluate pandemic-era learning losses and adjust priorities. For advocates of gender equity in STEM, the immediate imperative is not only to close performance gaps but also to repair the pipeline of interest that feeds into high school advanced-placement courses, extracurricular competitions and, eventually, college majors and careers.

At the workshop table, the Lego exercise offered a small but concrete example of the approach: hands-on experimentation, iterative problem solving, and a classroom environment that treats failure as a step toward discovery. Educators say such experiences can be foundational in persuading students, particularly girls, to persist in math and science after the disruptions of the pandemic.