U.S. Prisons Combat Evolving Drone Smuggling as Detection Tech Expands

Federal incidents rise; states expand drone-detection networks while grappling with regulatory limits and safety concerns

Drones are flying over U.S. prisons at increasing rates, with the Federal Bureau of Prisons reporting 479 drone incidents at federal facilities in 2024, up from 23 in 2018. The surge has stretched state systems, which cannot shoot down or jam drones under current federal aviation rules, leaving detection and confiscation as the primary tools for countering airborne contraband.

South Carolina officials say they are leading the nation in drone-detection and response at its medium- and maximum-security prisons. The state reported 262 drone incursions in 2022, up from 69 in 2019. Joel Anderson, director of the South Carolina Department of Corrections, says his team is building a nationwide model for timely alerts and rapid response. "We get assaulted nightly," Anderson said. "We get assaulted at multiple institutions at night." In South Carolina, once a drone is detected, staff receive a cellphone alert, and a dedicated drone-response team moves to the payload drop. Within minutes, the drone is often out of sight or the team has recovered the payload.

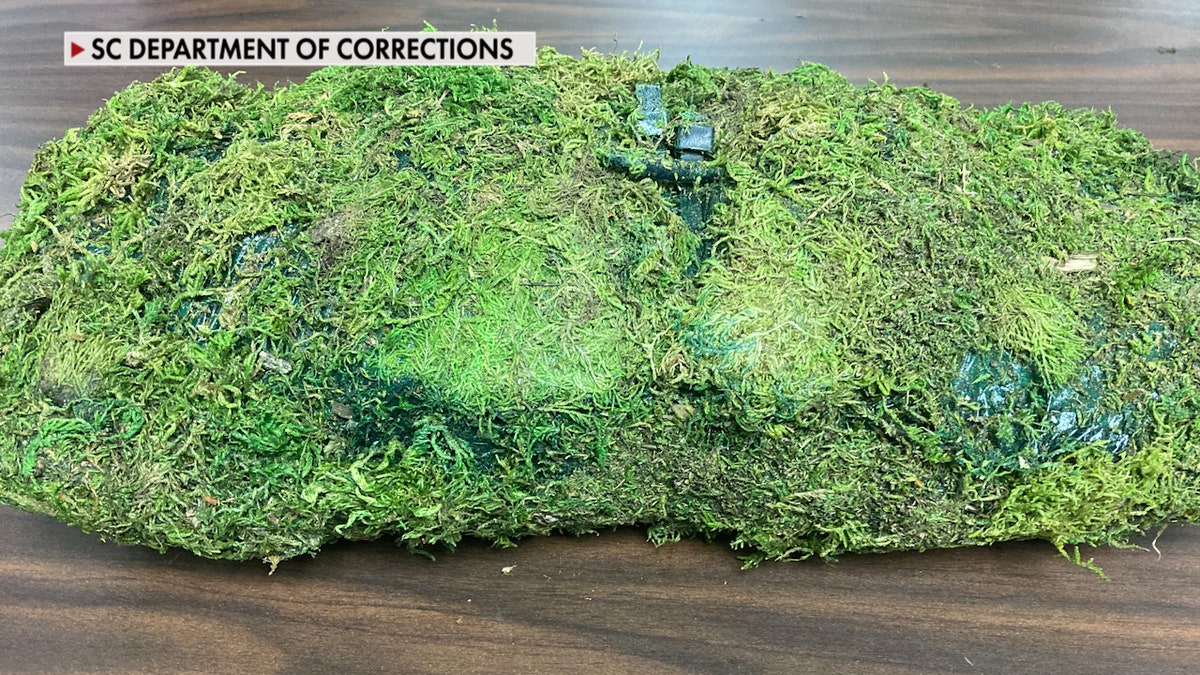

Anderson notes that drone smuggling has evolved quickly. Early drones carried about four pounds and flew as fast as 45 mph; today, heavy-lift drones can haul about 25 pounds and travel more than 75 mph, delivering opportune payloads over fences and sometimes returning to their controller multiple times in a single night. Many pilots are former inmates with networks inside facilities and access to illegal cellphones that coordinate deliveries. Smugglers also try to camouflage their payloads; for example, one drone payload was disguised with grass to blend into the yard, making detection harder from a distance.

The drone team confiscates disabled drones and downloads flight data from the devices. The records show paths, times, and images that investigators can use to trace a pilot to a residence or a business. The Federal Aviation Administration prohibits states from downing drones because they are considered registered aircraft, so agencies rely on detection and seizure rather than kinetic disruption. In some cases, authorities have recovered drones before they completed a delivery; in others, a drone has been tracked back to its operator’s location. Anderson notes that the safety risk of downing a drone could endanger people on the ground and inside facilities, including the potential to release lethal drugs if the drone crashes. He points to a case where a single incursion carried fentanyl that could have killed the entire prison system had it reached multiple living areas; "464 grams of fentanyl in one bag".

The FCC is weighing allowing radio-jamming technology to block inmate communications from inside prisons, a move supporters say could reduce drone-smuggling networks driven by illegal cellphones. At the same time, agencies emphasize that any countermeasures must be deployed carefully to avoid collateral disruption of legitimate services outside correctional facilities. In the meantime, analysts say, the need for robust detection networks, data analytics from flight records, and ongoing staff training remains urgent as drones become more accessible and adaptable in criminal hands. Fox News notes that South Carolina’s program has become a model for other states seeking to curb this evolving threat.

The broader question for lawmakers and security officials is how to balance rapid technological advances with safety and civil-liberties considerations. Experts say that while counter-drone measures will likely grow more sophisticated, they must be paired with preventive steps, including clamping down on illegal cellphones that enable coordination with outside accomplices. Some advocates argue that expanding lawful jamming and more advanced detection systems could reduce smuggling without creating new risks for nearby communities. Others caution that interference could affect legitimate communications, airspace operations, or emergency services if not properly regulated and geographically targeted.

As authorities push for smarter security tools, the underlying technology remains central: drones themselves are becoming more capable, compact, and affordable; detection networks are increasingly leveraging sensor fusion, geofencing, and analytics to identify patterns in flight activity; and data from drone flights—such as time stamps, routes, and imagery—can serve as a critical fingerprint for investigations. The ongoing challenge for corrections departments is to close the gap between rising threat levels and the legal and operational constraints that limit more aggressive countermeasures, while still safeguarding the public and staff.

Images embedded here illustrate the spectrum of the issue: from alerting personnel to the realities of payload camouflage, the visual record underscores why authorities view drone incursions as a persistent and evolving threat to prison security. As the landscape shifts, the balance between innovation, safety, and oversight will shape how prisons defend against this modern form of contraband and whether new policies will empower more proactive disruption or impose additional safeguards on counter-drone technologies.