Australian cybersecurity expert warns Chinese-made electric vehicles could be disabled or detonated remotely

Former government cyber adviser says connected vehicles and other China-controlled devices pose safety and national security risks amid rising Chinese EV sales in Australia

A former senior Australian cybersecurity adviser has warned that electric vehicles (EVs) linked to China could be remotely disabled or made to explode, calling the nation's exposure to Chinese-connected devices a major national security failure.

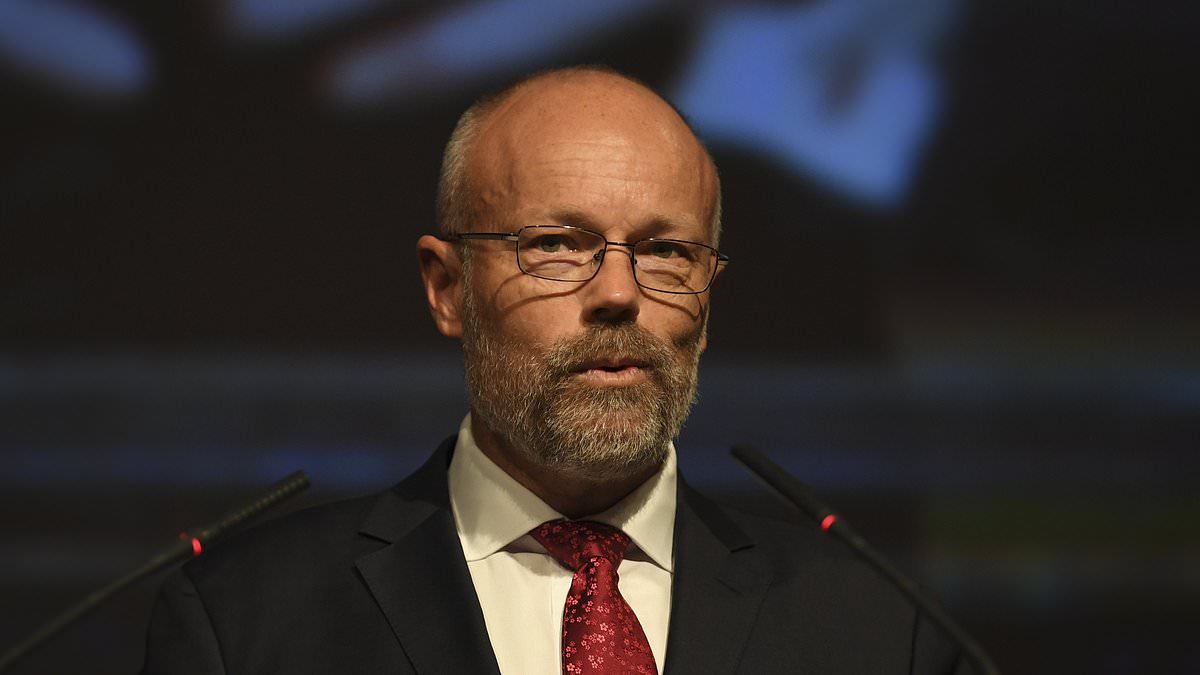

Alastair MacGibbon, who served as cybersecurity adviser to then‑Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and is now chief strategy officer at CyberCX, made the comments at the Financial Review’s Cyber Summit on Tuesday. He said connected vehicles are effectively "listening" and "surveillance" devices and urged a reassessment of policy that has allowed such products into Australian markets.

"The last decision of the National Security Committee of the Turnbull government was to take high‑risk vendors out of 5G networks," MacGibbon said. "Fast‑forward seven years and… potentially millions of [Internet of Things] or connected devices — not made in China, but controlled by China — are all through our systems." He urged that public officials be barred from using certain Chinese‑connected vehicles, saying the situation was "so dire".

MacGibbon outlined hypothetical scenarios he said illustrate the risks: removing safety features on household or vehicle batteries so they overcharge, remotely disabling cars during peak traffic to cause chaos, or turning off systems so vehicles could explode. He framed the issue as extending beyond privacy concerns to direct threats to safety and national security.

Experts and government officials have for years flagged privacy and security vulnerabilities in internet‑enabled cars, including those not fully electric. During Senate estimates late last year, Home Affairs Minister Tony Burke told senators he had to "take precautions" to avoid data collection through his own Chinese‑made EV. Home Affairs officials have said connected vehicles could collect data from paired phones, eavesdrop on calls and reveal occupants' movements through geolocation tracking.

MacGibbon’s remarks echoed concerns expressed by international policymakers. The Biden administration last year proposed a suite of rules that would in part bar Chinese‑made vehicles on safety grounds. Australian lawmakers have said they are watching those moves closely. Nationals MP Barnaby Joyce told Sky News in September that Australia should consider following the United States, asking whether vehicles that can be updated, tracked and are made in China might be used for a "malevolent" purpose.

The vulnerability argument has been extended to other household and infrastructure items, including rooftop solar panels and Chinese‑made hot water systems. MacGibbon and some other security commentators have said the risks inherent in internet‑connected devices could be exploited in a conflict to create widespread disruption.

Industry data show the rapid rise of Chinese manufacturers in Australia’s vehicle market. China now builds about 80 percent of all EVs sold in Australia, driven by falling prices and a wider range of models. In August, Australians bought more than 20,000 Chinese‑made vehicles, putting four Chinese firms in the national top ten for the first time, according to Federal Chamber of Automotive Industries statistics. Chinese brand BYD last month overtook Mitsubishi to become the sixth best‑selling car marque after sales nearly quadrupled compared with the previous August.

Security experts and some politicians have urged the federal government to review its approach to Chinese‑made EVs and other connected devices, calling for scrutiny similar to the assessments that led to a 2018 ban on so‑called "high‑risk" telecommunications vendors. The government has not announced a comparable national policy for vehicles and household Internet of Things equipment, and ministers have signaled the issue involves balancing consumer choice, industry competition and national security concerns.

Civil liberties and privacy advocates have also urged careful calibration of any policy response to avoid undue discrimination against products or consumers, while cybersecurity professionals continue to press for clearer standards and stronger technical safeguards for connected vehicles and home devices.

MacGibbon said the risks are immediate and require action. "Those cars that we talk about, whether they’re electric or not, are listening devices, and they’re surveillance devices in terms of cameras," he said. His remarks add to growing debate in Canberra over how to manage the security implications of rapidly expanding fleets of connected vehicles and other China‑linked technologies on Australian soil.