Courts backlog in England and Wales hits record levels, with 100,000 cases projected by 2028

Backlog in Crown Court reaches historic highs; funding cuts, the pandemic and legal-aid pressures are cited as drivers as reforms loom

More than 79,600 criminal cases are caught in the courts backlog in England and Wales, according to the latest figures from the Ministry of Justice. The Crown Court backlog has been at a record high since early 2023 and is projected to reach about 100,000 by 2028, a pace that could leave victims and defendants waiting years for justice in some serious cases. The government has signaled radical reforms to speed up the system, including removing juries from a number of trials, part of an effort to claw back ground after years of underfunding and disruption.

Delays are not just statistics. For many charged today, the path to trial could stretch into the next decade. The backlog’s growth has slowed every attempt to clear it, with some defendants facing openings in the system only to see their cases linger for months and years. The pace of justice affects victims seeking closure, defendants awaiting hearings, witnesses asked to return year after year, and the professionals who keep the system running. Officials say the present trajectory risks eroding public confidence in the ability of courts to deliver timely justice.

The government has pledged reforms aimed at speeding trials, including removing juries from certain cases to reduce trial length and the overall burden on court timetables. Justice ministers say non-jury trials could be used for some offences where juries are not essential, arguing that such changes would free up judicial time for more serious matters. Critics, however, warn that stripping juries from cases raises questions about fairness and transparency, and they note that reforms must be paired with sustained investment in the courts system.

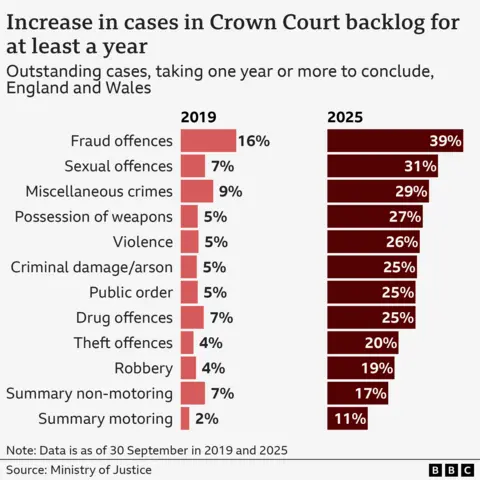

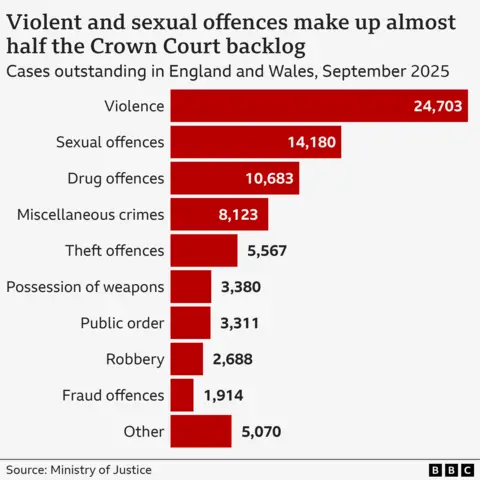

Key drivers of the backlog include a marked rise in long-running cases: roughly a quarter of violence and drug offences, many not requiring detention before trial, have been in the backlog for at least a year. More than 30% of sexual offenses are in the same bracket. By contrast, in 2019 there were about 200 sexual offences open for more than a year; now there are more than 4,000. The scale signals how far the system has shifted from pre-pandemic norms and how much the country depends on timely court processes to resolve serious criminal proceedings.

The root of the problem lies in funding. Beginning in 2010, as part of broader austerity measures, the Ministry of Justice absorbed large spending cuts. The coalition government reduced the MoJ budget, and today its spending sits at about £13 billion—roughly £4.5 billion lower in real terms than it would have been had spending kept pace with the average for other government departments. That gap has manifested across the system in fewer courtrooms, under-used facilities and a slower pace to move cases to trial.

Eight crown court centers and more than 160 magistrates courts were closed by 2022 as part of austerity-driven consolidation. Ministers also introduced a cap on the number of days judges are paid to sit in court, a policy intended to curb spending but which left some courtrooms effectively idle when no judge was available. In 2016-17 there were 107,863 of these sitting days; by the eve of the pandemic, the figure had fallen to 81,899.

The Covid-19 pandemic intensified the strain. All Crown Courts closed for two months during the first lockdown except for urgent and essential work, and when courts reopened many courtrooms could not be used for trials because they were too small to accommodate social distancing. The slowdown of trials during the pandemic created a backlog that has been difficult to unwind. One London example illustrates the broader trend: Blackfriars Crown Court, once a hub for serious organized-crime cases, was closed in 2019 with plans to sell the site. When cases were shifted to nearby Snaresbrook, they were quickly overwhelmed as demand surged during and after the pandemic.

To mitigate pressures, temporary Nightingale courts were opened to keep cases moving, sitting for about 10,000 days between July 2020 and 2024. They were not equipped to handle custody cases, however; many lacked secure facilities for defendants or adequate cells. Today there are five Nightingale courts remaining, with plans for their closure by March 2026. Reopening closed courts has also been part of the response, but it has not fully offset the losses from earlier cuts.

A further layer of difficulty comes from the legal aid system, which funds representation for defendants who cannot afford their own lawyers. The National Audit Office has documented a real-terms reduction in MoJ legal aid spending of about £728 million from 2012-13 to 2022-23. The Criminal Bar Association has observed a 12% decline in the number of barristers doing criminal work between 2018-19 and 2024-25. In 2021, officials urged an extra £135 million in funding for legal aid; the package was not viewed as sufficient by many in the profession and triggered months-long strikes by defence barristers the following year. The strikes disrupted court proceedings and contributed to a renewed backlog as cases stalled during walkouts.

The pressures on courts and defense come alongside changes in policing and evidence collection. After years of austerity, political emphasis on boosting police numbers created a mismatch: more suspects charged and sent to trial without a parallel plan to ensure courts could handle the higher volume. In addition, many serious cases now rely on extensive digital evidence—from mobile devices and online communications—that can require months of analysis before a trial begins. Prosecutors say the depth and complexity of digital evidence in cases such as sexual offenses have added months to preparation time, extending timelines and delaying hearings.

The backlog has a knock-on effect beyond the courts. Prisons in England and Wales are feeling the strain from rising remand populations: about 17,700 people are on remand, nearly double the number in 2019, and roughly 12,000 are waiting for trial. Remand cases constitute around 20% of the prison population. With fewer cases concluding quickly, the number of prisoners is projected to top 100,000 by 2030, a trajectory that raises concerns about crowded facilities and the ability to house or process inmates who have not yet been sentenced.

In response, the government under Sir Keir Starmer’s administration introduced an early release scheme for some offenders last year and pledged broader reforms aimed at reducing the time it takes to resolve cases. Officials argue that without comprehensive reforms to resources, staffing, and the use of technology, the backlog will persist, eroding the law’s ability to deliver timely justice and undermining faith in the system.

The court backlog is not just a domestic concern. It has implications for international perceptions of the UK’s rule of law, affects cross-border investigations and collaborations, and adds pressure on prosecutors and defense lawyers who must adapt to longer timelines and shifting priorities. Advocates say the path forward must balance urgent capacity with structural reforms: sustained funding for the MoJ and the courts, investment in legal aid to ensure robust representation, and a strategic approach to handling digital evidence and complex cases. Without these elements, the backlog risks becoming a steady feature of the justice landscape rather than an anomaly to be corrected.

The scale of the challenge is not in dispute among policymakers, practitioners, and researchers. The rise in long-running cases, the uneven reopening of facilities after the pandemic, and the fragility of funding streams have combined to create a structural deficit that has lasted years. As the government weighs reforms such as juror-free trials, the priority remains clear: restore a functioning, timely system that can deliver justice to victims, fair treatment to defendants, protection to witnesses, and stability for the professionals who operate England and Wales’s courts.

The path to that goal will involve difficult choices and sustained investment. While reforms may change how trials are conducted, the civil and criminal justice system will need to rebuild capacity, recruit and retain qualified lawyers, modernize case-management and evidence-handling processes, and ensure that resources match the demands of a modern, digital era. Only with a comprehensive, adequately funded plan can the backlog begin to shrink and the wheels of justice turn with the speed the public expects.