England and Wales court backlog reaches new high as MoJ projects 100,000 by 2028

Funding gaps since 2010, the pandemic, and staffing shortages have driven a record criminal court backlog, prompting reform proposals including jury-less trials to speed justice.

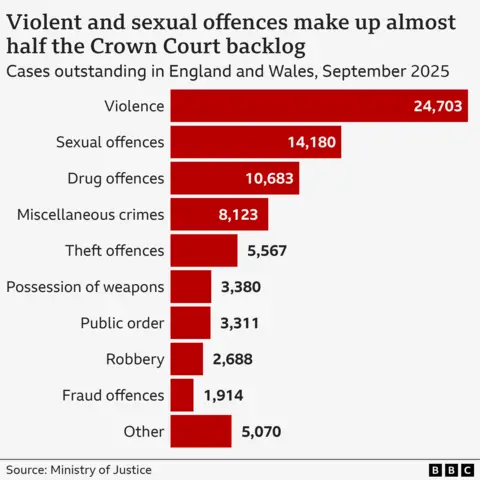

More than 79,600 criminal cases are stuck in the backlog in England and Wales, according to the latest Ministry of Justice figures. The Crown Court backlog remains at a record high since early 2023 and the MoJ projects it could rise to about 100,000 by 2028. For some serious offenses charged today, victims and suspects could wait years for a trial, with some cases unlikely to be heard before 2030.

About a quarter of violence and drug offences, many not requiring pretrial detention, have been in the backlog for at least a year. More than 30% of sexual offences have been in the system for at least that long. By comparison, in 2019 there were roughly 200 sexual offences open for more than a year; now there are more than 4,000.

So how did we get here? At the heart of this story is funding — and the lack of it. Since 2010 the MoJ budget has been cut in real terms. The coalition government pledged to balance the books and slashed the MoJ budget, leaving total spending around £13 billion today, about £4.5 billion lower in real terms than it would have been had it kept pace with the average government department, according to the Institute of Fiscal Studies. The cuts were followed by court closures: by 2022 eight crown court centres had closed and more than 160 magistrates courts were shuttered. Ministers also introduced a cap on the number of days judges are paid to sit in court, a move intended to reduce spending. When there is no judge, there is no hearing, and individual courtrooms sit idle even if a whole complex is backing up.

The Covid-19 pandemic then hammered the system. Crown Courts closed for about two months in the first lockdown except for urgent work, and when they reopened many courtrooms could not be used due to social distancing, slowing proceedings and fueling the backlog. Temporary Nightingale courts were created to keep cases moving from 2020 to 2024, sitting in non-traditional spaces. They handled thousands of days of hearings but could not deal with custody cases, and five Nightingale sites remain open through 2026. The result: the backlog intensified as pretrial work and trials moved more slowly. A telling example is Blackfriars Crown Court in London, which closed in 2019 as part of a plan to repurpose land and reduce capacity. Cases moved to Snaresbrook, but the rebound in volume amid the pandemic left it overwhelmed. In September 2019 Blackfriars had about 1,500 outstanding cases; by September this year that figure had risen to more than 4,200.

There have also been sharp shifts in the mix of crimes in the backlog. Before the pandemic, only about 5% of violence cases were more than a year old; now about a quarter are. Similar patterns are seen in drug offences and possession of weapons, with sexual offences showing a pronounced backlog growth as well.

The crisis is compounded by the state of the legal aid system. The National Audit Office has found a real-term reduction in MoJ legal aid spending of about £728 million between 2012-13 and 2022-23. The Criminal Bar Association reports roughly a 12% drop in the number of barristers doing criminal work between 2018-19 and 2024-25. In 2021 the government was urged to inject an extra £135 million into legal aid; the funding increase did not go far enough for many, triggering months of barristers’ strikes in 2023 and further disrupting proceedings.

The story is not just about lawyers; policing growth without parallel court capacity has fed the backlog. In 2019 the government pledged to hire 20,000 more police officers, which boosted prosecutions but did not come with a corresponding plan for the courts. Prosecutions now face longer pre-trial preparation, including the growing task of sifting digital evidence from mobile devices, which can add months to case preparation before a jury can consider the evidence.

The backlog also spills into the prison system. About 17,700 people are on remand in England and Wales, and nearly 12,000 are waiting to be tried. Remand prisoners account for roughly 20% of the prison population. The MoJ has warned the overall prison population could top 100,000 by 2030, a trajectory that would place additional pressure on the courts when remand handling hinges on case resolution. In response, authorities have rolled out early release schemes for some offenders, but those releases depend on timely case resolution in the courts, creating a cycle that can stall further if remand cases dominate the queue.

Against that backdrop, policymakers have begun signaling wider reforms to the criminal courts. The government has floated changes aimed at speeding up justice, including removing juries from some trials in England and Wales. Proponents say jury-free trials could shave days or weeks off proceedings for certain cases, while critics warn of reduced public oversight in serious crime. The debate is ongoing as ministers seek to prune the backlog without compromising fairness.

The scale of the challenge is evident in the numbers and in the lived reality of defendants, witnesses and prosecutors. With no swift fix in sight, the system continues to grapple with how to balance speed, fairness and safety while delivering justice to those who rely on it the most.