Inside Britain's asylum hotels: life, risk and uncertain futures

A BBC File on 4 investigation details four UK asylum hotels where families and single men live in cramped, improvised conditions as the government moves to end the program by 2029.

Britain’s asylum-hotel system is drawing renewed scrutiny as a BBC File on 4 investigation documents residents living in four temporary hotels across the country, where families and single men endure cramped rooms, improvised kitchens, and repeated moves amid a government pledge to end the program by 2029.

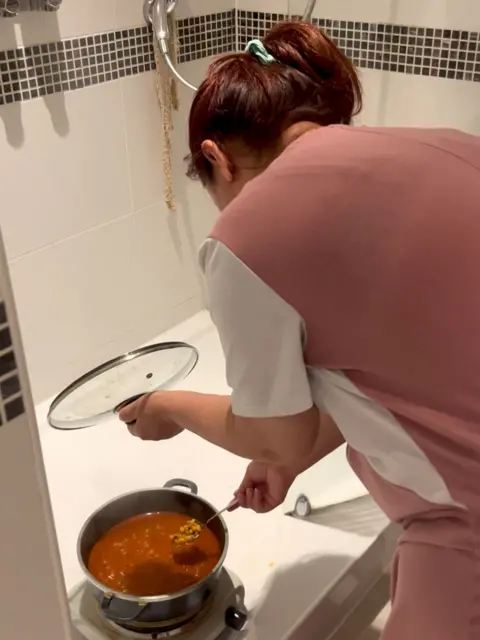

In rooms that look smart in online photos, the reality can be very different. In one hotel, a family is cooking in a shower tray while an electric cable runs to a makeshift hob. A pan full of oil spits as herbs and spices drift through the corridors, and a smoke alarm has been sealed tight with plastic bags. The setting is illegal and unsafe, residents say, but they prefer it to the free hotel restaurant fare they say makes them feel ill. “Everybody, they’re cooking in their rooms like this,” one resident explains, adding that many people do it undercover because the hotel food is not welcomed by all.

I visited four migrant hotels this summer to try to understand what life is like for those living and working there. Two sites housed families, the others were primarily single men. The hotels were never intended to be long-term homes. To protect residents and staff, the exact locations are not disclosed. In the rooms, review-site gloss hides wear and tear and the accumulation of possessions from months and years of occupancy. Reception has largely given way to security desks, and outside there are bollards warning the public away. In family hotels, prams crowd the reception and babies and toddlers abound, with little communal space for play. In one hotel, a security guard named Curtis showed me a makeshift running track he built in an unused car park for the children; he has scoured a storeroom for bikes and repaired them so they can be used by the kids.

Some residents have lived in the hotels for years while waiting for asylum decisions, and some have had babies while in the system under the belief that giving birth would hasten their case or secure a British passport. The Home Office says it has no figures on how many children have been born in asylum hotels. One of the first babies I meet is held aloft by a father who says the child was born in the UK and will be a “British baby.” In reality, birth within the UK does not automatically guarantee a route to stay, though there are safeguards to prevent immediate deportation for babies and their mothers. The Refugee Council’s Jon Featonby notes that while safeguards exist, there are still cases where families can be deported after birth, complicating the lives of children who have known no other home.

Kadir and Mira, a couple who fled Iraq, are among the families I met. They live in two adjoining hotel rooms with their baby in one and their 12-year-old daughter and 14-year-old son in the other. They arrived nine years ago after being targeted because Kadir worked as a translator in his home country. The Home Office initially rejected his case for lack of proof; two appeals failed before a third is underway. Kadir says he wants to work but would not take a job illegally, though he knows other residents who do. He points to Mohammed, an Afghan man who arrived only recently and says he found a job before reaching the UK because his cousin was already working here. Mohammed is earning about 20 pounds a day on shifts that can last ten hours or more. He says his family owes money to smugglers, and he has no choice but to work illegally to support them.

Across the four sites, security and transportation patterns emerge. Some residents come and go in ways that suggest work outside the hotels. Delivery bikes are often parked nearby, and vans pick up residents for work. In July, the Home Office conducted a nationwide crackdown on illegal delivery drivers, stopping 1,780 individuals for questioning and arresting 280 for illegal working. The Home Office says staff at the hotels do not monitor employment, but Curtis the security guard says that without meaningful occupation, residents will seek work elsewhere because there is little else to do. Taxi travel is a constant feature: residents receive a weekly bus pass for one return journey, but most other travel—doctor visits, appointments, or moving between hotels—is arranged by taxi through the hotel reception’s automated system. A knee problem for Kadir once required a 250-mile taxi ride to a consultant who had treated him before; the return trip reportedly cost about 600 pounds. “Should the Home Office give me the ticket for the train? This is the easy way, and they know they spend too much money,” he says. “We know as well, but we don’t have any choice. It’s crazy.”

I accompanied Mira and Shayan, their daughter, on a walk to a local chemist to pick up a prescription. The outing placed them under the gaze of protesters who chant “Go home!” at asylum hotels. Police escort them as they pass. Shayan, now 12, says she would like to speak with the protesters but that hotel staff keep her from going to them. She and her brother say the school bus is a potential risk because protesters might attempt to board it. “Me and my friends have always wanted to go up to them and speak to them face-to-face. What is their problem with the kids as well?” Shayan asks, explaining the instability of school placement and the constant need to adjust to new surroundings. “Once we get settled in a place, then they move us, and then we’ve got to learn where we come from, like, learn that area, go to a new school, make new friends, and then once we’ve done that, they move us again.”

The families’ future at the hotels remains unsettled. Since speaking with me, Kadir and his family have been told they will be moved again, to two hotels in different cities. The baby and the parents are slated for one location, while Mira, Shayan, and Roman, the boy, are to be relocated to another hotel nearly 200 miles away. They have refused to go, and Kadir has already been told he has lost his weekly benefit and may be deemed intentionally homeless. The government’s broader plan to wind down asylum hotels by 2029 remains in place, with about 32,000 people housed in hotels across the UK—down from a peak of around 51,000 in 2023.

The investigation underscores the contrast between glossy hotel listings and the lived reality behind them: crowded rooms, improvised meals, and the constant tension of uncertainty about where a family will sleep next month. The government has pledged to end the use of asylum hotels by 2029, but for those living inside them, the days are defined by a chain of moves, a struggle to access services, and a daily effort to sustain family life while their asylum claims proceed. As the BBC’s reporting shows, the human cost of policy design is felt not in the abstract but in kitchens built in shower trays, lines at chemist counters, and the buses and taxis that carry families from one uncertain milestone to the next.

The system’s vulnerabilities are not only administrative. Protests this summer at asylum hotels, including sites in Epping, Essex, reflect public anger and concern about what some see as an open-ended stopgap. The stories of families like Kadir’s illuminate how the policy’s reach extends beyond paperwork: it shapes livelihoods, access to education for children, and the daily choices of where to live and work. The Home Office says it is reviewing options as it works toward the 2029 deadline, while security and local communities navigate the tensions that come with large numbers of people living in temporary accommodation.

At the heart of the piece are the residents’ voices: the children who grow up inside hotels, the parents who fight to protect their families, and the staff who balance duties to residents with the constraints of a national policy. The BBC’s reporting emphasizes that the asylum system’s scale—tens of thousands of people, many of them families with young children—has created a set of logistical challenges that cannot be solved by short-term fixes alone. The government’s stated goal is to reduce reliance on asylum hotels, but the path to that objective remains contested and complex, leaving families to navigate a system where every move can alter their futures.

For Kadir, Mira, and their children, the question is whether the next move will bring stability or another setback. The family’s reluctance to relocate highlights a broader tension within the policy: moves are sometimes necessary to meet capacity and policy objectives, but they also disrupt schooling, healthcare access, and social connections for vulnerable households. The Home Office notes the objective of reducing the use of asylum hotels and expanding alternative housing options, but the logistical and humanitarian complexities of moving thousands of people across the country are significant and ongoing.

The investigation also highlights how travel arrangements are integrated into daily life in the hotels. Although residents receive limited bus access, taxis are frequently used to attend medical appointments, retrieve prescriptions, and attend interviews. A knee problem that led to a long taxi ride to a consultant, with a return fare believed to be around £600, illustrates the cost and time burdens imposed by the current system. Residents describe a pressure to do whatever is needed to remain with family and avoid becoming separated, even as the financial and logistical strains mount.

In this environment, the line between waiting for an asylum decision and navigating daily life becomes blurred. The hotels’ interiors may appear clean and modern in online reviews, but the stories inside reveal a cycle of displacement, legal limbo, and resilience. For the families living in limbo, the next move is never merely a location change. It is a continuation of a struggle to secure safety, stability, and a sense of belonging in a country that has granted them temporary shelter but continues to determine their long-term fate.