Inside UK asylum hotels: life, delays and protests as government pledges closure by 2029

BBC File on 4 Investigates visits four hotels housing asylum seekers to document daily life, safety concerns and the human impact of a system in flux as the government aims to end the program by 2029.

UK officials say the use of asylum hotels is set to end by 2029, a policy shift aimed at replacing temporary housing with more permanent solutions. A BBC File on 4 Investigates team visited four hotels sheltering asylum seekers to illuminate daily life, the pace of decision making on cases, and the tensions that have grown as the program has stretched for years. The reporting captures moments of resilience alongside safety concerns and logistical challenges in a system that remains in transition.

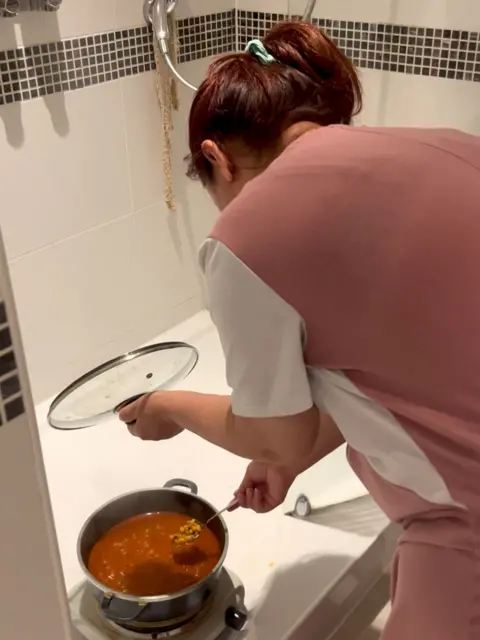

In one family’s routine, a meal is cooked inside a hotel room shower, with an improvised hob and makeshift kitchen setup that relies on taped and improvised wiring. A bathroom sensor that would normally alert to smoke has been sealed in plastic, a sign of risk that residents say they have accepted because restaurant meals provided by the hotel can be unsatisfactory or unsafe for some. Residents describe cooking in their rooms as a widespread practice, done discreetly because hotel life grows heavier the longer people stay. Across the four sites, families and single men alike share a sense of uncertainty as moves from one hotel to another are announced with little notice.

The four sites studied by the BBC host a mix of families and single men. The rooms themselves appear modern in online reviews, with sofas, double beds and en suite bathrooms, but the reality is a different picture. Security desks and barriers have replaced traditional reception desks, and corridors with baby strollers and play areas reveal the realities of long stays. In the family hotels, prams and toddlers are common in reception spaces, and a makeshift running track carved from an unused car park offers a rare space for children to play amid the hotels’ gray surroundings.

The scale of the program is sizable and evolving. The Home Office says the use of asylum hotels has fallen to about 32,000 residents across the United Kingdom, down from a peak near 51,000 in 2023, as the government promises to end the hotels by 2029. The policy goal is to move residents into more durable housing and to speed up asylum decision timelines, but the long waits for decisions are a central thread running through the stories in the hotels. Children are a prominent and visible part of these sites, with many babies and young families creating an ongoing demand for school placements, doctors and social services in a system trying to adapt to year after year of occupancy.

There are no official figures on how many children have been born in asylum hotels, a gap the Home Office has acknowledged. Advocates say births in the hotels complicate removals and underline the tension between safeguarding children and enforcing immigration policy. Jon Featonby of the Refugee Council notes that while births may not guarantee a future in the country, safeguards exist to protect young families from being deported solely because a child was born in the UK.

Kadir and Mira, a couple who featured in the reporting, arrived in the UK from Iraq with their two older children and have since welcomed a baby. They say their case was initially rejected for lack of proof, followed by two unsuccessful appeals and now a third under way. The family occupies two adjoining rooms: one for the parents and their baby, another for their 12-year-old daughter and 14-year-old son. Kadir says he would like to work but will not do so illegally, though he knows others who supplement their government support with illegal work to send money home.

Mohammed, an asylum seeker from Afghanistan, describes securing a job soon after arrival through family connections and earning around 20 pounds a day for long shifts. He says financial pressures, including debt to people smugglers, push families to consider illegal work while they await decisions. The BBC found that some residents travel for work and that a steady flow of taxis and courier deliveries circles the sites. In July, a government crackdown targeted illegal working by delivery drivers, stopping 1,780 individuals for checks and leading to 280 arrests, with 53 people subject to review of their support as a result.

The hotel staff say they are not responsible for policing residents’ work, but security personnel describe the daily realities of life that extend beyond the building’s doors. A security guard named Curtis explains that without structured activities or legitimate work options, residents often seek paid work in the informal economy. Taxicab movements link the hotels with hospital appointments, legal hearings and social services, a system that can produce long or unusual journeys. Residents are issued a one-way bus pass per week for a single return trip; other travel requires a taxi booked through an automated system, with evidence of appointments shown at reception. A knee problem that required medical follow-up, for example, led Kadir to a 250-mile taxi ride to see a consultant, with a return fare estimated at 600 pounds. He questions why the Home Office cannot fund a train ticket instead, highlighting the financial strain of logistics that the government says is necessary to move people between sites.

The human impact sits alongside the operational questions surrounding asylum hotels. In the face of protests this summer, residents and supporters have voiced anger and fear that the hotels symbolize a broader sense of uncertainty for people who have spent years waiting for decisions. One city protest near an Essex hotel drew attention to calls to close the hotels once and for all, with demonstrators arguing that the system leaves families in limbo and imposes heavy costs on the state and on residents. For some children, the protests have added another layer of stress, while the staff warn of the strain on day-to-day life inside the hotels.

Among the residents is a 12-year-old girl who says she wants to engage with protesters but that she cannot cross the line between the hotel and the outside world. She describes a life in which frequent moves disrupt school, friends and places of belonging, and she explains the difficulty of holding on to a sense of normalcy when the family is moved again. The children have grown up inside the walls of the hotels, with some describing a life spent largely within the building and its corridors, as the family waits for a decision that could determine their future in the country.

As the BBC interviewed residents, Home Office officials acknowledged the ongoing relocation plan and the possibility of moving families to new sites. Since the interview, Kadir and his family were told they would be moved again, to two hotels in different cities. The husband and wife would be housed separately from their children, and the family described a risk that the weekly benefit could be stopped, raising the possibility that they could be deemed intentionally homeless. The family has refused to relocate and maintains that they will continue to seek stability in the country. The future for this family, and for many others, remains uncertain as policy, resources and personal circumstances intersect in a complex and evolving national debate.