Inside UK asylum hotels: life, uncertainty and the push to end the program by 2029

BBC File on 4 reveals daily life in four asylum hotels across the United Kingdom, where families cook in shower trays, journeys to doctors are measured in miles and pounds spent on taxis, and residents fear what comes next as the system …

An investigation into the United Kingdom’s asylum hotel system shows residents living in cramped, improvised spaces, with makeshift cooking setups and long, costly travel to access services, underscoring the strain of a program the government says will end by 2029. The government says about 32,000 people are housed in asylum hotels nationwide, down from roughly 51,000 in 2023, a shift linked to ongoing policy changes and the pledge to end the use of hotels for asylum housing.

The four hotels visited for File on 4 included both family sites and single-occupant sites, where rooms appear modern in online reviews but carry the wear of months and sometimes years of continuous occupancy. Behind the reception desks are security stations, bollards, and signs indicating public access is restricted. In family-focused hotels, the corridors are crowded with prams, babies, and toddlers, while in other sites there are long lines of men moving between rooms and services. In one hotel, a security guard named Curtis showed a makeshift running track he set up in an unused car park for children, and bikes he repaired from a storeroom to keep them active.

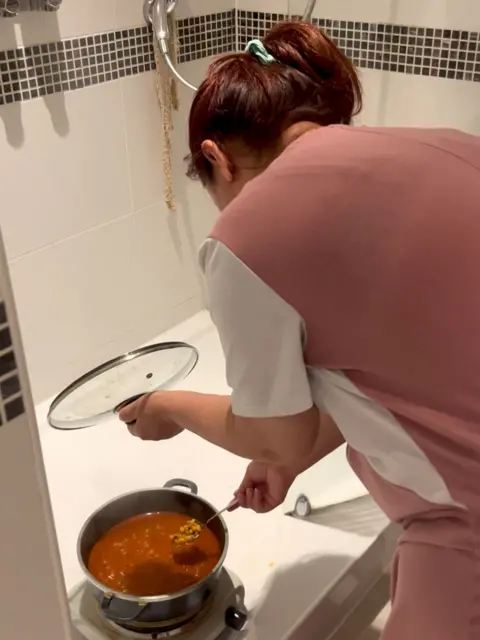

Behind closed doors, residents describe a reality that rarely shows up in glossy hotel photos. In one room, a family cooks on a makeshift stove in the shower tray, an electric cable extended into the bathroom, and a smoke alarm sealed off with plastic bags. The setup is illegal and unsafe, but residents say they would rather cook themselves than eat the free hotel meals, which they describe as “chips and chicken nuggets” and which they believe can make them feel ill. “Everybody, they’re cooking in their rooms like this,” one resident said, adding that many do it undercover to avoid trouble.

The BBC spoke with families who have waited years for decisions on their asylum claims and with people who have had babies while living in hotels, sometimes under the impression that a baby could help secure a path to British citizenship. The Home Office says there are no figures on how many children have been born in asylum hotels. Jon Featonby of the Refugee Council notes safeguards exist, but the possibility of deportation remains even for those with babies.

Kadir and Mira, a couple from Iraq who were living with their two older children in adjoining rooms and recently welcomed a baby, describe a long, peripatetic journey through the asylum system. They have been moved between hotels across the country for nine years. The Home Office initially rejected Kadir’s case for lack of proof, followed by two unsuccessful appeals; a third appeal is under way. The family’s daily life is shaped by limited space and a desire to work, which Kadir says he would do only legally. He introduces the investigation to Mohammed, from Afghanistan, who says he found a job before arriving in the UK and now earns about £20 a day on shifts that can last up to 10 hours. He says families borrow money from people-smugglers and that sending money home is a constant calculus in a system that restricts legal work and leaves many residents with little other option.

In all four sites, people come and go at all hours, suggesting a steady stream of workers who may be contributing to the local economy in informal ways. The Home Office has conducted a nationwide crackdown on illegal working among delivery drivers, stopping 1,780 individuals and arresting 280 in July, with 53 people having their support reviewed as a result. Staff at the hotels say it is not their job to police work, but Curtis the security guard notes that without meaningful activities, residents often seek work elsewhere.

The funding and logistics of travel add another layer of complexity. Residents receive a weekly bus pass for a single return journey, but for any other necessary travel—the doctor, hospital, or appointments—taxis are arranged through the hotel reception. An upcoming NHS appointment can trigger a lengthy taxi ride that is both costly and impractical. Kadir recounts a knee problem that required a 250-mile round trip to see the consultant who treated him previously, with a return fare cited at around £600. He questions whether the Home Office should fund a train ticket instead, arguing that the system compels people into expensive, inefficient options.

Children’s lives reflect broader tensions. A 12-year-old girl named Shayan and her 14-year-old brother Roman traverse a life spent moving between hotels, learning new schools, and confronting protests that have become a regular feature near asylum sites. The family’s future is uncertain: after this interview, they were told they would be moved again—separated into two hotels across nearly 200 miles—but they have refused to relocate, fearing further disruption and the potential loss of weekly benefits. Shayan spoke about wanting to engage with protesters to understand their concerns, while acknowledging the fear of buses and strangers who might threaten the routine they have built.

In August 2025, protests escalated around an asylum hotel in Epping, Essex, following a crime that amplified tensions in the community. Protesters demand the closure of such hotels, while residents and staff caution that the upheaval of relocation could further destabilize families already navigating a fragile legal process. Journalists are typically denied access to asylum hotels, but this investigation received access through migrant contacts who had traveled across the English Channel from France.

While the rooms themselves can appear clean and well-appointed on review sites, the long-term occupancy and living conditions reveal a different picture. There is little communal space beyond a few lounges, which means children spend more time in hallways than in playgrounds. A recurrent theme across locations is the sense of perpetual transition: residents move from hotel to hotel, area to area, and school to school, with each move marking another step in a drive toward a decision that could alter their lives for years to come.

The government’s stated objective is to end the use of asylum hotels by 2029, a policy shift that follows years of public debate and local protests. The Home Office maintains that the system serves a necessary function in processing asylum claims, while critics argue that it traps vulnerable people in precarious conditions and fuels insecurity and exploitation. The latest figures show the population in asylum hotels has declined since 2023, but the pace and geography of removals, relocations, and policy changes remain highly uncertain for families who have built lives on the move.

Kadir and Mira’s story is emblematic of a broader arc: a family that fled danger in Iraq, sought safety in the UK, and now faces an unsettled future shaped as much by administrative decisions as by personal resilience. They say they want to work and contribute, but the current rules—and the cost of keeping a family together—make that path difficult to navigate. The next steps for them—and for thousands of others living in asylum hotels—will unfold against the backdrop of a national policy that aims to move away from hotel-based accommodation toward a different approach to processing asylum claims, with a target of 2029 in sight.

As the Home Office continues to revise policy and funding, the human cost of the asylum hotel system remains a pressing concern. Families like Kadir’s continue to endure relocations, ongoing legal battles, and waits that stretch into years while the state weighs how best to balance security, humanitarian obligations, and the practical realities of shelter in a country that has long promised to protect those who seek refuge within its borders.