Recognising Palestinian statehood opens another question — who would lead it?

Britain, Canada and Australia join a growing wave of recognitions at the United Nations, highlighting both momentum for statehood and the persistent questions of borders, governance and leadership amid Gaza's devastation and a long-runni…

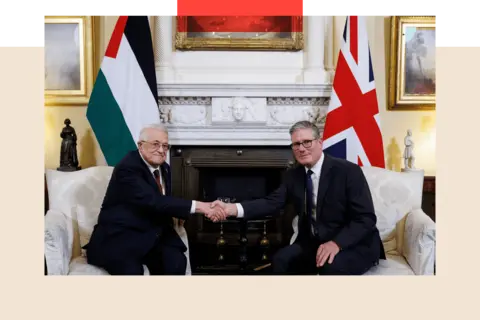

Britain, Canada and Australia joined a growing list of states that have said they will recognise a Palestinian state at the United Nations, a move supporters say could sustain momentum for a two-state solution even as the conflict intensifies in Gaza and the West Bank. In a message circulated on social media, UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer said: "In the face of the growing horror in the Middle East, we are acting to keep alive the possibility of peace and of a two-state solution. That means a safe and secure Israel alongside a viable Palestinian state — at the moment we have neither." The new recognitions come after Belgium, France and other partners had already signaled similar intentions, and they reflect a broader international push to bolster formal engagement with a Palestinian state in the absence of a peace deal.

The move is widely understood as more than symbolic. More than 150 countries have recognised Palestine in some form since the 1980s, but the addition of the United Kingdom, along with Canada and Australia, is viewed by many observers as a potent diplomatic signal. Still, the question of what a recognised state would look like in practice remains at the center of the debate. Even among supporters of recognition, the practical implications are contested, because recognition alone does not guarantee progress toward a negotiated settlement. A British government official briefed on the matter stressed that recognition should be coupled with tangible steps and accountability to the principles laid out in the New York Declaration, including steps toward Palestinian unity, elections and the unification of Gaza and the West Bank.

From a legal standpoint, the recognition raises a familiar but stubborn set of questions about statehood under the Montevideo Convention. The convention lists four criteria for statehood: a permanent population, a defined territory, a functioning government, and the capacity to enter into international relations. Palestine can reasonably claim two of those: a permanent population and the capacity to engage with other states, as evidenced by its diplomatic activity. But there is no agreed final border, nor a single, functioning government that effectively administers a unified territory. The West Bank and Gaza Strip have been geographically separated since 1948, and since 2007 have been governed by two rival authorities: the internationally recognized Palestinian Authority in the West Bank and Hamas in Gaza. Even the Gaza conflict has left large swaths of the territory devastated and in flux, complicating the prospect of any stable, internationally recognized borders.

The fourth criterion, a functioning government, is the most acute hurdle. The Palestinian Authority (PA) has long faced legitimacy challenges, corruption allegations and a leadership crisis that predates the current conflict. Elections have not been held since 2006, and the PA’s grip on Gaza waned as Hamas consolidated control there. The result is a political landscape in which the West Bank is governed by the PA and Gaza by Hamas, with no viable mechanism for a unified Palestinian leadership that could credibly speak for a sovereign state.

Weighing in on the leadership question, observers point to a chorus of concern that there is no obvious successor to Mahmud Abbas, who is approaching 90 and has led the PA since 2005. A 1994 framework created the PA through the Oslo process, but the mid-2000s split between Hamas and Fatah left the Palestinians without a single, widely accepted governing authority. Palestinians themselves have reflected on the absence of renewal. Diana Buttu, a Palestinian lawyer and former adviser, has argued that a new generation and a new leadership are long overdue. She has stressed that the core problem is not just who leads, but whether the leadership can deliver an end to internal division and credible governance that can support a state.

Palestinian public opinion provides some guidance on possible leaders. A recent poll by the Palestinian Centre for Policy and Survey Research found that, among those surveyed in the West Bank, 50% would choose Marwan Barghouti as president, a figure well ahead of Abbas in his current role. Barghouti, a Fatah veteran, has long been viewed as a potential alternative to Abbas but has been imprisoned by Israel since 2002 on charges related to past violence attributed to him during the second intifada. His political standing underscores the tension between popular support for reform-minded leadership and the practical barriers posed by his detainment and by the broader security situation.

The idea of a future Palestinian leadership also intersects with the political dynamic inside Israel. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has repeatedly opposed Palestinian statehood in its current form and has suggested that any future arrangements must reflect security realities on the ground. In February 2024, he stated publicly that he had opposed creating a Palestinian state that would threaten Israel’s existence. In recent months, Israeli authorities have advanced settlements that would redraw the map in East Jerusalem, moving to further isolate parts of the West Bank from one another. Such moves complicate any prospect of a contiguous Palestinian state and raise questions about whether any leadership could effectively claim sovereignty in a future Palestinian territory.

The international dimension adds further complexity. The United States retains a veto on UN recognition votes and has signaled continued opposition to a unilateral move that would redefine the status of Palestine without a negotiated settlement. In August, Washington tightened visa controls on Palestinian officials in a move linked to its broader stance on the conflict. Washington has also shown support for alternative approaches, including a long-term arrangement centered on security and governance rather than a straightforward path to statehood. The Trump-era Riviera Plan, though never adopted, proposed a long-term US ownership position in Gaza and emphasized a reformed Palestinian self-governance framework rather than a direct PA role—an approach that critics say would ignore Palestinian sovereignty.

Against this backdrop, the New York Declaration adopted by the General Assembly and endorsed by a wide coalition of states, including Britain, remains a focal point. The declaration calls for tangible, time-bound steps toward a peaceful settlement of the question of Palestine, with particular emphasis on unifying Gaza and the West Bank, supporting the PA, and pursuing Palestinian elections as part of a broader reconstruction program for Gaza. It also highlighted the Arab world’s support for a unified Palestinian authority and an international reconstruction effort. Yet for all its symbolism, the declaration does not by itself resolve the practical obstacles to statehood, including the status of Jerusalem, final borders and the role of Hamas in any future governance.

For Palestinians and their backers, the question remains whether recognition today translates into a credible pathway to sovereignty. Diana Buttu cautions that symbolism without action may not produce meaningful change; she argues that the real test is whether recognition can translate into progress toward unification of Gaza and the West Bank, a revived PA capable of governing a state, and actual steps toward elections and a sustainable peace process. As she put it in discussions with BBC colleagues, the aim should be to prevent further bloodshed and to create a political environment in which a Palestinian state could emerge through negotiation rather than unilateral declaration.

If a Palestinian state does eventually emerge, it is likely to resemble a mosaic more than a classic nation-state, with Gaza and the West Bank connected by political arrangements rather than contiguous territory, and with security and governance arrangements that reflect ongoing regional and international complexities. The path to statehood is unlikely to be linear. It will hinge not only on international recognition but on how leadership evolves, how borders are defined, and whether a credible, unified government can be formed capable of engaging with other states and international institutions. In the meantime, the recognition moves may help to keep alive the possibility of peace and a two-state solution, even as the parties grapple with a stubborn reality: Palestinian leadership that can unify rival factions and deliver governance remains a central, unresolved prerequisite for any sustainable state.

As the international community weighs next steps, the balance between symbolic recognition and practical progress will continue to shape the conversation about Palestine’s future. Supporters insist recognition can unlock new diplomatic momentum and bring attention to the humanitarian needs of Gaza and the Palestinian people, while critics warn that without a credible leadership and a clear path to a negotiated settlement, it risks becoming a footnote in a decades-long conflict. The question of leadership, more than any single policy move, may ultimately determine whether a Palestinian state can ever be realized, or remain a lasting aspiration with no final resolution in sight.

In governance terms, the coming period will test whether the international community can translate recognition into reforms that address the roots of the crisis: a fractured political landscape, a stalled peace process, and a humanitarian emergency that has left Gaza’s population in dire condition. For Palestinians like Diana Buttu, the urgent task remains not only who leads, but how to halt ongoing suffering and advance a framework for a durable political arrangement. As she observes, preventing further killing should take priority over any statehood agenda, even as other actors press ahead with recognition as a step toward a broader settlement.