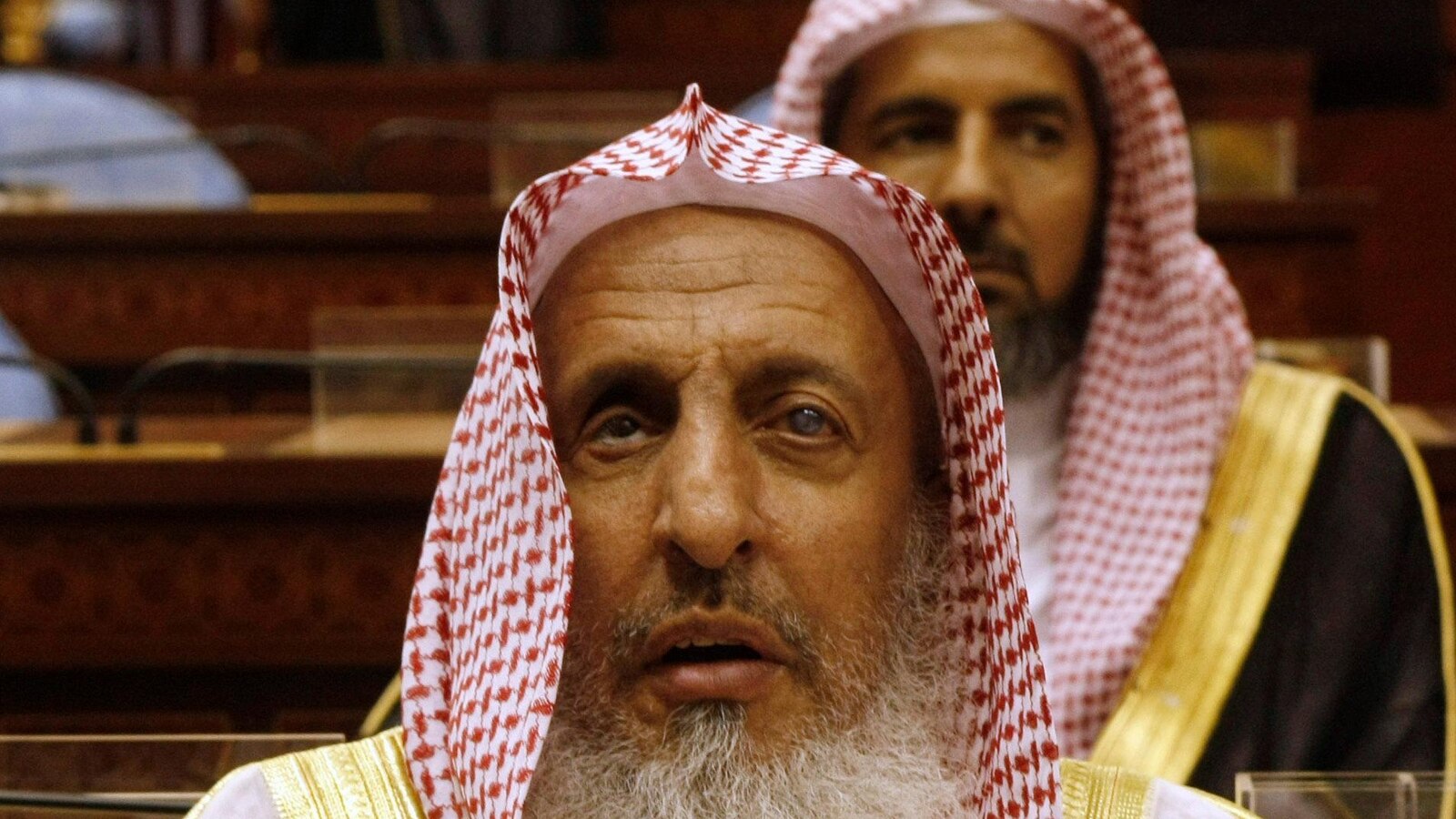

Saudi Arabia’s Grand Mufti Sheikh Abdulaziz bin Abdullah al-Sheikh dies

Long-serving religious authority helped shape Saudi policy during decades of social change

Saudi Arabia’s grand mufti, Sheikh Abdulaziz bin Abdullah al-Sheikh, died Tuesday, state media reported, in his 80s. The death removes one of the kingdom’s most influential religious figures at a time when Saudi leaders have promoted social and cultural reforms while maintaining strict ideological guidelines. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman attended funeral prayers for the late mufti in Riyadh, according to official accounts. The Saudi Royal Court issued a statement praising his contributions to Islam and Muslims, while state media provided no immediate cause of death.

Sheikh Abdulaziz served as the kingdom’s grand mufti from 1999, installed by King Fahd, a position that placed him at the apex of Sunni religious authority in Saudi Arabia. For more than a quarter century, he helped shape the official interpretation of Islam in a country that hosts Islam’s two holiest sites, Mecca and Medina, and that has long used religious authorities to legitimize state policies. While closely aligned with the ruling Al Saud family, he publicly denounced extremist groups such as ISIS and al-Qaida, and he repeatedly affirmed the state’s commitment to security and unity under a single government.

Yet the mufti’s long record also included statements that drew international scrutiny. In 2004, he criticized the use of mobile phone cameras, saying they could be exploited to “spread vice in the community.” He also weighed in on Christian-related issues, such as during Pope Benedict XVI’s 2006 remarks linking some of the Prophet Muhammad’s teachings to “evil and inhuman” conduct, which drew global attention. In 2012, when asked about Christian churches in Kuwait, he reportedly said it was “necessary to destroy all the churches of the region,” a stance that was later walked back by aides amid condemnation from Christian leaders.

The mufti’s rhetoric extended to Shiite Muslims, and he commented after clashes with Iran that Shiites were not Muslims, referring to them as Majuws—an older term tied to Zoroastrianism and fire-worshipers. Those remarks echoed the broader sectarian tensions in the region and were later tempered as Saudi Arabia pursued its strategic interests, including improving ties with neighboring states and stabilizing the region. He also condemned what he described as the “fake jihad” of militant groups in 2007, and after a 2014 attack in Saudi Arabia, he asserted that the country would remain united under a single government.

Over time, the strong social policing that accompanied Wahhabi-influenced governance began to give way to a broader modernization push championed by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. The mufti’s public stances on gender and social mixing—once described as “evil and catastrophe” in some contexts—softened as women began driving in 2018 and as commercial entertainment venues expanded under state reforms. Yet the modernization came alongside a crackdown on dissent and a tightening of political space that some attributed, in part, to the crown prince’s consolidation of power. The mufti’s influence appeared to wane as these reforms accelerated, even as he continued to serve in his quasi-official capacity during the pandemic.

During the coronavirus outbreak, he urged adherence to public health measures, warning that ignoring distancing and related guidelines could lead to serious consequences for the faithful and the broader community. His role, however, remained largely ceremonial in the sense that the king and crown prince steered policy, while the religious establishment, including the grand mufti, served to provide legitimacy and guidance aligned with state priorities.

The royal court’s tribute underscored the lasting significance of his office, noting that he contributed to the service of Islam and Muslims throughout his tenure. The development comes as Saudi religious authorities prepare to navigate succession and potential shifts in the balance between conservative doctrine and the kingdom’s evolving social contract. The funeral, attended by senior royal aides and religious officials, signaled the end of an era for a figure who helped frame a state that has sought to modernize while maintaining doctrinal continuity.

As Saudi Arabia continues to calibrate its domestic reforms with its regional strategy, the death of the grand mufti marks a moment of transition for the kingdom’s religious establishment. How the next generation of clerics interprets and communicates the state’s religious narrative remains to be seen, but the office’s influence is unlikely to disappear entirely, given the continued fusion of faith and national policy in Saudi governance.