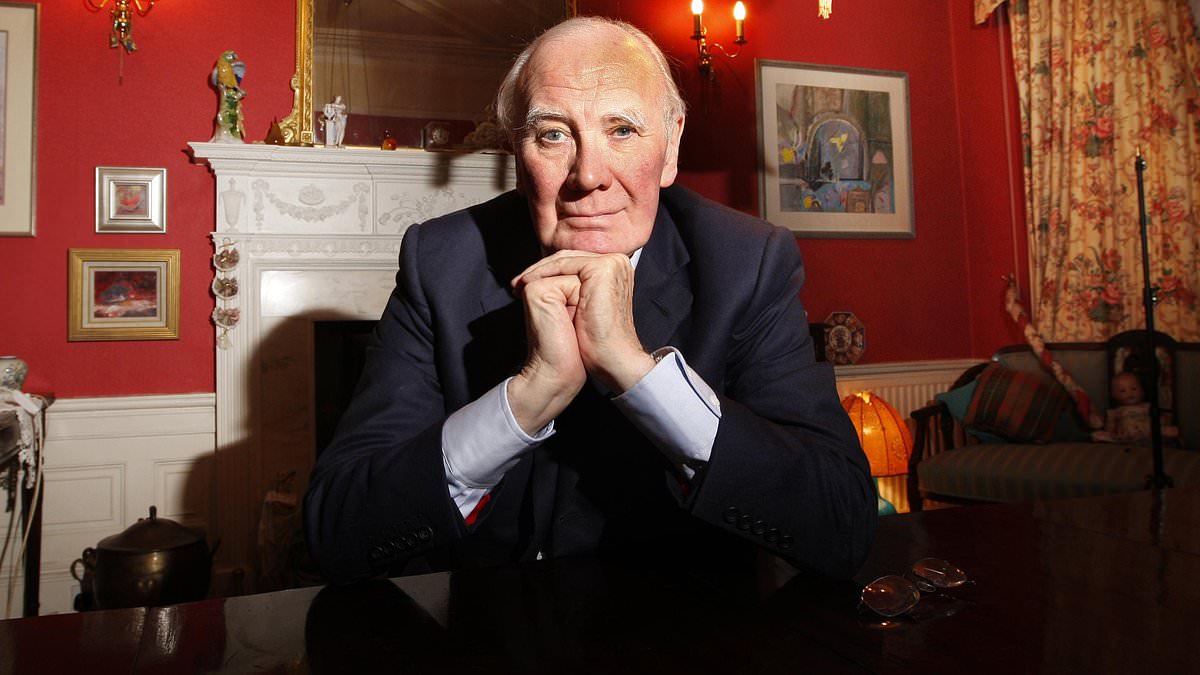

Sir Menzies Campbell, Liberal Democrat leader and multilateralist, dies

Tribute honors a courteous, principled public servant who shaped debates on Iraq, the UN and humanitarian crises

Sir Menzies Campbell, Bar on Campbell of Pittenweem, a former Liberal Democrat leader and long-time figure on Britain’s foreign policy stage, has died, colleagues said. He was remembered for a courteous demeanor, a rigorous legal mind and a steadfast commitment to multilateralism and international law as the world navigated conflicts, humanitarian crises and the evolving liberal order.

Born in Glasgow in 1941, Campbell rose from athletics corridors to the House of Commons, a path that reflected his belief in discipline, fair play and public service. He studied at Glasgow and Stanford universities and built a career in law before entering Parliament. His early years were marked not only by academic achievement but by sport: he broke a half-century sprint record, competed in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and the 1966 Kingston Commonwealth Games, and became an Amateur Athletic Association champion twice. His nickname among admirers was the “Flying Scotsman,” a reference to both speed and dignity that many colleagues said mirrored his approach to politics. He would later serve as chancellor of the University of St Andrews for 19 years, a post that underscored his longstanding ties to education and public life.

Campbell entered Parliament as MP for North East Fife in 1987 and quickly established himself as a principled voice on foreign affairs and defense. Over 14 years on the front bench, he became a trusted policy broker for the Liberal Democrats, shaping debate on Britain’s role in NATO, defense budgeting and international engagement. He led the party in the wake of Charles Kennedy’s resignation for 18 months, mentoring colleagues while navigating internal tensions about age, direction and how best to balance liberal ideals with pragmatic governance.

As a foreign policy maven, Campbell’s worldview was formed in the liberal, multilateral currents of the 1960s and 1970s: a suspicion of unchecked power, a belief in universal human rights, and a preference for the United Nations to anchor international action. He was known for holding a well-informed, legalistic approach to global issues—one that prized due process and the rule of law over knee-jerk reactions. That stance informed his long-standing skepticism toward unilateral military interventions and his insistence that any use of force be justified within an international legal framework. In this vein, he often pressed governments—across party lines—on the complexity of post-conflict reconstruction, humanitarian considerations, and the consequences of policy decisions on civilians.

His most widely discussed stance during his political prime was on the Iraq War. Campbell argued against the rush to war, not out of opposition to removing Saddam Hussein per se but due to concerns about legal justification, the sufficiency of UN backing and the likely consequences for regional stability. Six months before coalition planes entered Iraqi airspace, he urged the Labour government to seek a fresh UN resolution with binding obligations. He warned that if Saddam failed to comply with inspections, military action might become necessary, but he did not consider the invasion a foregone conclusion or a proper substitute for international legitimacy. In the early days of the war he criticized the government’s handling of reconstruction, insisting that remaining uncertainties about governance, security and humanitarian needs needed more robust, law-based planning.

Campbell’s approach stood out not for the headlines of opposition but for the texture of his critique: patient, legally grounded, and willing to challenge decisions across the aisle when they contravened international norms. He pressed ministers from both Labour and Conservative cabinets, and his analyses were widely regarded as informed by real-world experience and a careful reading of international law. That steadiness was characteristic of a political career built on a belief that influence should be exercised with restraint and respect, even amid disagreement.

In foreign affairs and defense, Campbell’s philosophy favored multilateral action, regional stability and human rights within a framework of procedural legality. He supported the UN-led approach to conflict resolution and development, while acknowledging the limits of Western power and the need to address the grievances of the developing world. This worldview sometimes put him at odds with more interventionist impulses, but it also earned him respect across party boundaries for measured dissent and fidelity to principle. He carried those convictions into his later years in the Lords, where his questions and speeches continued to emphasize humanitarian concerns, including the worsening humanitarian situation in Gaza.

Off the podium, Campbell’s life was marked by devotion to family and academia. He spoke openly of his long marriage to Elspeth Campbell, who predeceased him in 2023, describing her as a crucial adviser and an intellectual partner whose dinners and conversations shaped his worldview. The couple—married for 53 years—shared a connection that colleagues said grounded him amid political tumult. Elspeth’s lineage, as the daughter of Major General Roy Urquhart of World War II renown, added a layer of public history to their life together. Campbell’s commitment to public service extended beyond Parliament; his long tenure as chancellor of the University of St Andrews linked him to a generation of students and scholars who benefited from his steady leadership and advocacy for higher education.

The political landscape in which Campbell rose—one of close political combat, rapid media cycles and evolving threats to liberal internationalism—has since shifted. Yet observers say his legacy endures in the tone with which he conducted himself: principled, courteous, and unfailingly civil even when in opposition. He embodied a form of liberalism that prized constitutional norms, dialogue across divides and a willingness to test ideas against evidence and international law rather than slogans.

In reflecting on his career, analysts and colleagues emphasize that Campbell’s contributions were not about a single policy package or a ministerial portfolio. Rather, they reflect a persistent, underappreciated ethos—a commitment to the integrity of public life, to rigorous debate, and to the belief that the world’s problems require patient, multilateral solutions grounded in law and human rights. As the global liberal order continues to adapt to new challenges—security threats, climate change, humanitarian crises—the example he set remains a measure of what principled public service can look like in difficult times.

Sir Menzies Campbell’s passing closes a chapter in British politics marked by a particular blend of civility, curiosity and fortitude. His long public service—through parliament, the Lords and the university—leaves behind a standard of conduct that colleagues say will be hard to replace in a climate where rancor and expediency often overshadow deliberation. In a world that has grown more fractious and more complex, his legacy is remembered as a reminder that character and conscience can guide policy through even the most contentious debates. His life, the public and private sides alike, was a testament to a public service ethos that valued dignity, humility and perseverance, and it was, as many colleagues observed, his longest and final race—and he won it by a mile.