UK court halts first planned France removal after modern slavery claim

A High Court injunction delaying the deportation of a 25-year-old Eritrean highlights legal and operational obstacles to the UK‑France returns agreement.

A High Court judge on Tuesday granted an interim pause of at least 14 days that prevented the Home Office from putting a 25‑year‑old Eritrean man on a flight to France under the UK‑France returns arrangement, after the man said he had been a victim of modern slavery.

The man, who cannot be named for legal reasons, arrived in the UK on a small boat in August. Home Office officials initially rejected his asylum claim and told him he could and should have sought protection in France, but he also asked for protection as a victim of trafficking and modern slavery, saying he suffered harm in Libya before reaching the UK. Trafficking assessors within the Home Office found his account weak but, under UK rules, that rejection was not final and can be followed by a request for reconsideration.

During the hearing the senior judge repeatedly asked why the man could not make any further representations, including gathering medical evidence, from France. The case turned when the department's own trafficking officials indicated they would not expect the claimant to pursue those representations from abroad, a stance that undermined the Home Office's argument that removal could proceed. That concession factored in the judge's decision to block the planned 9 a.m. flight from London Heathrow, at least temporarily.

Government lawyers had argued in court that if this removal were blocked it would weaken the deterrent effect of the policy. The judge's interim order does not permanently stop removals but illustrates the legal safeguards in UK law designed to protect people who say they have been trafficked. Under current rules, anyone who presents a reasonable claim that they may have been a victim of trafficking is entitled to a minimum 45‑day "recovery and reflection" period. A formal determination can take much longer and, if the claimant succeeds at later stages, they could be removed from a removal list for a protracted period while appeals and reconsideration proceed.

Officials inside government had privately expected a number of deportation flights to France under the 'one in, one out' scheme to depart this week. The pause in this case meant that the steady flow of departures envisaged by ministers did not materialise. Officials warn that other cross‑Channel arrivals may make similar trafficking or modern slavery claims, particularly because many people who travel by small boat pass through countries such as Libya where abuse and trafficking are widespread.

Conservative voices hailed the court intervention as a vindication of their long‑running criticisms of the Home Office. Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch told LBC: "We told you so." Labour figures said the ruling did not amount to a fatal blow to the returns deal. Labour's Liz Kendall told BBC Breakfast the scheme had never been presented as a "silver bullet" and that a single interim judgment would not stop the agreement from going ahead.

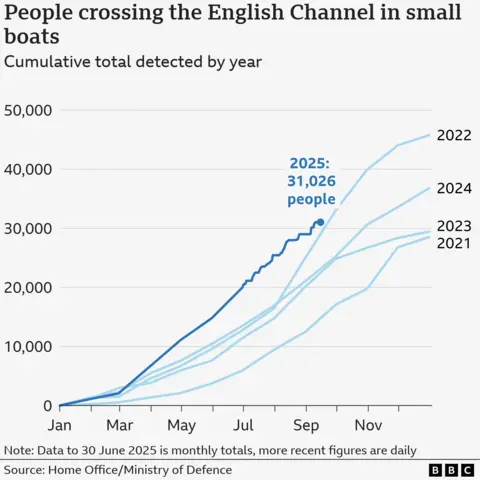

The returns agreement, described by ministers as a way to deter unlawful crossings by removing people who could and should have sought asylum in France, was flagged as one of the previous home secretary Yvette Cooper's policy priorities. The plan now sits with her successor, Shabana Mahmood, who early in her tenure signalled a tougher communications line on illegal migration and pledged to do "whatever it takes" to address small boat crossings.

Legal experts and officials say the case exposes the practical challenge of rapid removal flights in an environment where trafficking and modern slavery safeguards apply. The Home Office comprises separate teams: those who make trafficking assessments and those who organise removals. Where those teams reach different conclusions or where assessors indicate a claimant needs further time or support, planned deportations can be delayed.

It is too early to tell whether this interim ruling will bog the returns scheme down in repeated legal actions of the kind that dogged the earlier Rwanda policy, which was cancelled after the change of government. The single injunction, applied to a single claimant, does not legally forestall further flights; ministers may still proceed with removals where they judge legal requirements have been met. But ministers and officials acknowledge the political risk: the government’s own lawyer warned in court that blocking removals could diminish the policy’s deterrent effect, and this hearing will be cited by opponents as evidence of the scheme's operational fragility.

For now, the removal was halted while the claimant is given at least 14 days to provide further material in support of his trafficking claim. The longer‑term outcome will depend on subsequent trafficking assessments, any reconsideration decisions, and whether other courts are asked to review similar injunctions. The decision underlines how immigration policy, domestic trafficking law and operational practice intersect, and how those intersections can slow or complicate swift implementation of returns arrangements.

Officials said they remain committed to making the France returns arrangement work but acknowledged the complexity of cases that involve alleged trafficking or modern slavery. Ministers will need to navigate both legal protections for vulnerable people and political pressure to show removals are taking place as part of wider efforts to curb Channel crossings.