UK free-speech row boils over as political and tech forces clash

Debate widens from parliamentary exchanges to social-media policy, with international scrutiny and domestic safety concerns shaping the conversation

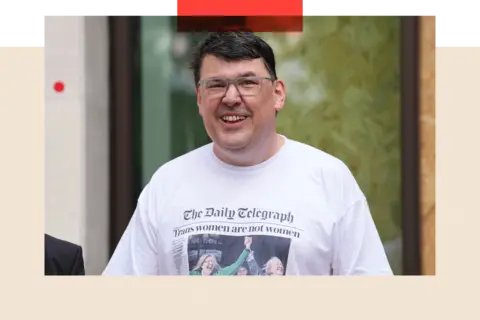

The debate over freedom of speech in the United Kingdom has moved from a simmering controversy to a high-stakes confrontation, drawing international attention as political rhetoric, policing decisions, and tech-company policies collide. In a recent confrontation that reached American lawmakers, Reform UK leader Nigel Farage asked a US congressional committee, “At what point did we become North Korea?” His inquiry framed the UK’s free-speech debate as a battle over what can be said in public, blasting what he called an “awful authoritarian situation we have sunk into.” He cited the arrest of Father Ted co-creator Graham Linehan over remarks about “a trans-identified male” in a female-only space, arguing that the UK is drifting toward a regime that punishes dissent. The moment underscored how far the conversation has traveled from Westminster to Washington and back again.

Farage spoke as part of a broader chorus voicing concern about limits on expression, a thread that runs through recent political and cultural clashes in Britain since the rise of social media. His deputy, Richard Tice, faced questions on Radio 4’s Today about whether Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer is comparable to North Korea’s Kim Jong Un. Three times, Tice avoided a direct equivalence, saying Farage was using an analogy. Yet the incident highlighted how even a calculated distancing from extremes can be treated as a proxy for a larger dispute over speech, safety, and power.

A string of cases has sharpened the focus on how online platforms and authorities regulate speech. One widely discussed episode involves Lucy Connolly, a Northampton former childminder married to a Conservative councillor, who posted an abhorrent message on X calling for people to “set fire” to hotels housing asylum seekers after a July 2024 murder in Southport. The post, viewed hundreds of thousands of times during a period of real threat, led to Connolly’s 31-month prison sentence for inciting racial hatred. She pled guilty to publishing and distributing “threatening or abusive” material, but the sentence — served at 40% before release — became a touchstone for those who argue that social-media amplification can turn odious remarks into a political issue. The episode helped some observers view the public square as a space where the boundaries of free speech and responsibility are constantly renegotiated. Connolly herself later described the incident publicly, reflecting on the intense spotlight such posts generate when they meet algorithms designed to maximize reach.

Connolly’s case sits at the intersection of individual responsibility, platform policy, and policing. The online environment has evolved rapidly since the mid-2000s, and the responses of large technology companies have shifted the ground under debates about free expression. After Elon Musk purchased Twitter and rebranded the platform as X, the company undertook changes to content moderation that Musk described as moving away from what he calls “the woke mind virus.” On Facebook and Instagram, Mark Zuckerberg likewise adjusted rules governing speech and community standards. In this environment, even a remark that might once have circulated in a private chat can be amplified widely by algorithms, a point highlighted by Lilian Edwards, an emeritus professor at Newcastle University, who noted that Connolly’s post was “accelerated by the algorithm.”

The policing of speech remains a central question for policing and policy makers. Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Mark Rowley has warned against relying on enforcement alone to solve online-content problems, saying, “It’s a nonsense to pretend that with all of the (online) content out there that enforcement is the answer.” His point echoes a broader legal debate: while the Human Rights Act protects free speech, it does so as a “qualified right.” Lorna Woods, a professor of internet law at the University of Essex, explains that government restrictions must be proportionate and “necessary in a democratic society.” The aim, she says, is to draw lines between harmful or criminal conduct and unacceptable but non-criminal expression, a distinction that proves difficult in practice when the line between harmful rhetoric and incitement, harassment, or violence is itself contested.

Former deputy prime minister Sir Nick Clegg has argued that the UK is “out of whack” with other countries on free speech, urging a hard look at whether the balance has swung too far toward policing speech. “Surely part of the definition of being in a free society is people say ghastly things, offensive things, awful things, ugly things, and we don’t sweep them under the carpet,” he said. His comments reflect a broader worry that overzealous moderation could chill legitimate debate and that the public should be able to express controversial views without fear of disproportionate punishment.

Public opinion on the matter adds another layer of complexity. A YouGov survey conducted earlier this month found that 61% of Britons prioritized keeping people safe online over absolute free speech, while 28% valued free expression above safety. The results suggest a strong public preference for reducing online abuse and threats, even as many respondents also acknowledged the costs of excessive censorship to democratic discourse. Anthony Wells, a YouGov director, notes a generational dimension: younger people often express concerns about safety while recognizing the value of open debate, a tension that underpins much of the current discourse.

The debate has also echoed across the Atlantic, where high-profile tensions around free speech in the United States feed into British discussions. The assassination of a prominent conservative figure in Utah this month intensified debates about the boundaries between free expression and incitement, while American commentators argued about how to reconcile First Amendment protections with calls for accountability. Tim Snyder, a historian critical of certain approaches to free speech, distinguishes between “free speech” and “me speech.” He argues that many powerful individuals claim robust protections for themselves while seeking to silence those with whom they disagree, a pattern he says undermines the broader public good. Snyder’s critique resonates with ongoing concerns in the UK about who gets heard and who is heard to silence others.

As the rhetoric grows more heated, observers emphasize the importance of listening as a core element of free speech. The British public’s experience of listening to different viewpoints — and the ability to verify information independently — helps anchor a more resilient democratic process. The BBC InDepth team stresses that the right to express oneself must be balanced with responsibilities to avoid harm, a balance that requires ongoing dialogue among lawmakers, courts, platforms, and the public. The question remains whether the UK will recalibrate the current framework to protect both safety and free expression without tipping toward censorship or allowing hate to flourish unchecked.

The public conversation continues, with policymakers and platform operators facing a demanding task: to uphold the core values of free speech while ensuring that speech does not endanger vulnerable groups or incite violence. As Nick Clegg and other political leaders have suggested, the country may need to rethink where those lines are drawn and how they are enforced, in light of technological realities and evolving social norms. In a world increasingly connected by digital networks, the UK’s approach to speech could serve as a test case for other democracies wrestling with similar questions. The stakes extend beyond national policy: they touch on how societies listen to one another, how information is shared, and whether public discourse can remain robust in the face of political pressure, online amplification, and evolving definitions of harm.